Full Dress, Half Dress, and Half Full Dress are terms seen frequently in fashion prints of the Regency period. I have found no definitions of those terms in any of the ladies’ magazines of the period, so one must assume they were common terms understood by the magazine’s readers, and needed no explanation.

Definitions of the terms, however, are fairly easy to interpret, based on the prints using those labels.

Full dress would have been the most formal of all evening wear, for both men and women. Full dress was worn only for very formal occasions, such as a ball or a formal reception or party. For women, prints labeled “Evening Dress” or “Ball Dress” would fall under the umbrella of Full Dress. There were also many prints with the specific label “Full Dress.”

There does not seem to be much distinction between these three labels. In the later part of the period, when hemlines fluctuated, the longer hemlines seem more often associated with an “evening dress,” which may indicate that the shorter lengths were for dancing, making it less likely for the woman to trip over her skirts. But for the most part, Full Dress, Ball Dress, and Evening Dress styles seem to be interchangeable.

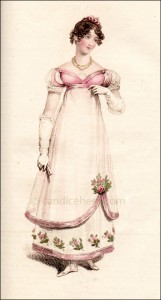

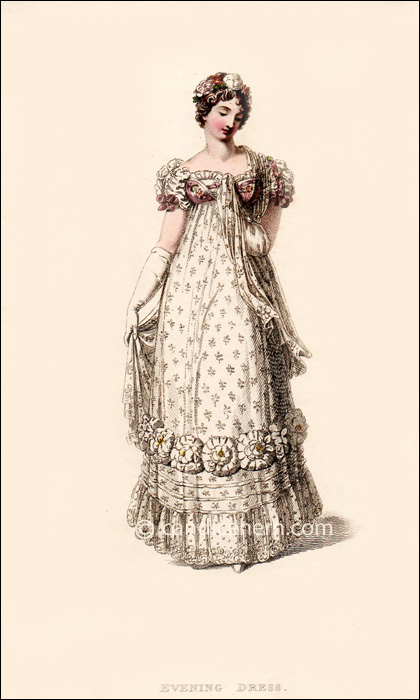

You can see by a quick look at the prints that the overall style of the dress remains similar throughout the period: a slender vertical silhouette with a high waistline.

There are changes, of course, from year to year, and even, if you believe the ladies’ magazines of the period, from month to month.

Overall, there is a gradual shift from a simple classical style to a more Gothic, heavily ornamented style. Only a few years after the last of the prints shown here, the era of the vertical silhouette is over, with skirts widening and sleeves ballooning to enormous proportions.

White remains the favorite color for dresses throughout the period, and is almost universal in the early years, 1800 – 1805, when the classical ideal was still dominant. Other colors seen in the prints are typically pastel shades, often seen in slips or underdresses beneath sheer fabrics. Brighter, bolder colors were often used in accessories and trimmings. Only the occasional bold color was used for the body of the dress.

The most prevalent fabrics for evening dresses are satin, crepe (always spelled crape), and sarsnet. These would be used for the main body of the dress, or for a slip or underdress. Layered dresses were prevalent throughout the period, likely due to the sheerness of many of the fabrics. Various delicate, diaphanous fabrics were used for overdresses, including fine India muslin, lace, gossamer net, imperial crepe, tulle, and figured or spotted gauze. For example, Figure 3 shows a crepe dress over a white satin slip; Figure 5 shows a white crape petticoat over a white satin slip; Figure 6 shows a lace dress over a white satin slip; and Figure 7 shows a white lace dress over a blush-colored satin slip.

A formal evening dress might include a train throughout the period, though is it more prevalent in the earlier years when skirts were longer in general. (See Figures 1 and 2.) Skirts stay rather long until after about 1806-1807 when hemlines appear to just skim the floor. (See Figure 3.) By 1815, hems have risen to show hints of ankle. (See Figures 5 and 7.) Some rather dashing ensembles show more than a bit of ankle and seem quite short to modern eyes. In the last few years of the period, hemlines move slightly up or down, but always some inches above the floor.

Necklines are typically very low for evening dresses throughout the period. Bosoms were much on display in the evening.

Waistline heights fluctuate randomly, as prints the same year will often show very high and very low waists (although all waistlines are well above the natural waistline) The waistline for evening dress gets generally quite high after about 1814, reaching its highest levels around 1817. (See Figure 7.) With the low necklines, an 1817 bodice can sometimes appear miniscule, at least in the prints. After that time, waistlines in general begin to fall, though evening dress continues for a while to show relatively high waists.

Long sleeves are more prominent in the very early years, ie through 1801-5, where they are generally quite tight and molded to the arms, but show up occasionally throughout the period in fuller variations. Short sleeves end just above the elbow in 1800 through about 1805. (See Figures 1 and 2), and get progressively shorter. Short puffed sleeves begin to be prominent for evening dresses around 1806 (a few years earlier in France), and continue throughout the period.

The skirts from 1800-1806 are still somewhat full, hanging from the body in loose draperies the in the classical style of ancient Greece and Rome, with most of the fullness gathered in the back. (See Figures 1 and 2.) During the next ten years, skirts remain rather narrow, almost tubular, without any fullness. Around 1815, the silhouette begins to take on a definite A-line or bell-shape, with the increasing width of the bottom of the skirt. (See Figures 5, 6 and 7.)

The decoration at the hem of evening dresses, if any, stays rather simple through the first decade of the century. From 1800 through 1803, the form is very classical and pure, with little or no embellishment. From about 1804, lace and ribbon trim at the hemline begin to be more popular, and by around 1811 is prevalent in almost every print. By 1814, the hemline becomes enhanced with a true flounce, ie a row of applied trim of lace, ribbons, braiding, piping, French knots, beading, etc. By 1815, with more post-war influence from the French who had been adorning hems for many years, the flounce becomes deeper, with more elaborate Gothic decoration, including deep swags and festoons, and continues to dominate the skirt from 1816 and beyond. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the overly fussy flounces of those years.

Gloves were always worn with evening dress. Most of the prints in my collection show white gloves for evening. The rare print will show a pale pink or yellow pair. With short sleeves, the gloves are always long, ie just over the elbow. They are worn looser than modern gloves. Figures 3 and 4 clearly show how loose the top of the glove was. In most prints the gloves often appear to be falling down the arm, bunched up below the elbow. The description of the print shown in Figure 4 says: “White gloves of French kid, falling below the elbow.”

Clearly the gloves shown in all the prints are above-elbow length, but are seldom actually worn above the elbow, but are instead allowed to loosely fall down the arm. French prints show a much tighter long glove, often held up with ties or ribbons.

All sorts of jewelry was worn with evening dress. Things to note are that bracelets are almost always shown in pairs, and very often worn on the upper arm, above the glove line. (See Figure 3) Bracelets worn on the wrist were worn over the glove. Necklaces of all sorts were worn, with long, heavy chains being popular in the earliest years, 1800 through about 1804. Layers of varying lengths of necklaces becomes popular after about 1813. (See Figure 4.) Earrings of all types are worn, with hoop earrings very popular throughout the period.

Shawls were often shown with evening wear. (See Figures 3, 4, and 6.) Considering the thin fabrics of the dresses, a woman would need something to keep warm! Shawls are often from Kashmir, typically very large, and frequently woven in a paisley pattern. Often a white or pale pastel dress is shown with a bold-colored shawl. In warmer months, shawls of silk, gauze, fine India muslin, or other lighter-weight fabrics are seen in the prints. The size of the shawl is largest at the beginning of the period, 1800 – 1803, and again after 1816, where they look to be as large as 6-8 feet long. During the middle years, they vary in more moderate sizes.

Shoes for evening were always a form of slipper. The prints show ladies with such unnaturally tiny feet that the shoe is not much defined. An exception is Figure 3, where the tiny shoes are shown with blue stripes. The magazine text for the print in Figure 6 describes the shoes as “white satin slippers richly embroidered in coloured silks,” and yet we cannot see the shoes at all. Even so, they are almost always described. The prevalent materials are satin and kid.

For more information on fashion prints, see these sources:

- Alison Adburgham, Women in Print: Writing Women and Women’s Magazine from the Restoration to the Accession of Victoria, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1972.

- Irene Dancyger, A World of Women: An Illustrated History of Women’s Magazines 1700-1970, Gill and Macmillan, 1978.

- Jody Gayle, Fashions in the Era of Jane Austen, Publications of the Past, 2012.

- Madeleine Ginsburg, An Introduction to Fashion Illustration, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1980.

- Vyvyan Holland, Hand Coloured Fashion Plates 1770-1899, Batsford, 1955.

- Doris Langley Moore, Fashion Through Fashion Plates 1771-1970, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1971.

- Sacheverell Sitwell and Doris Langley Moore, Gallery of Fashion 1790-1822, Batsford, 1949.

- Cynthia L. White, Women’s Magazines 1693-1968, Michael Joseph, 1970.

In Just One of Those Flings,

In Just One of Those Flings, Beatrice wears an evening dress of celestial blue with full short sleeves trimmed with knotted beading, over which she wore a Polonese robe of gossamer net trimmed with lace and more knotted beading.