The first folding fans were made around 1000 AD in Asia, probably China, and were brought to Europe by Portuguese traders in the early 1500s. The first European folding fans were likely produced in Spain or Italy, but fan-making soon spread throughout Europe. The Guild of Fan Makers was established in England in the early 17th century, and the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers was formed in 1709.

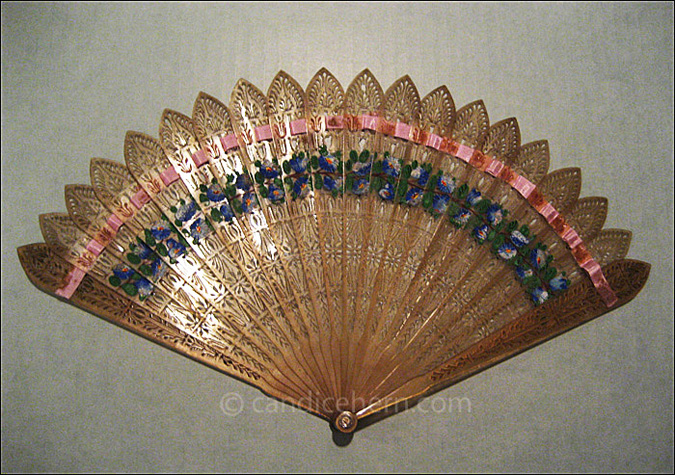

Figure 1 – Ivory fan of identically pierced sticks, cut in a delicate lacy pattern. Sticks threaded with ivory silk ribbon, and held together by an ivory rivet. c.1790-1810

The most common folding fans consist of sticks of identical length held together at the bottom with a rivet, with a curved leaf of paper, silk, lace or other material glued to the sticks and pleated.

The second most common type of folding fan is the brisé fan, consisting only of decorative sticks with no pleated leaf. (The term brisé — “broken” in French — has been used for this type of fan only since the early 20th century.)

The sticks of a brisé fan are typically carved or pierced, and held together by a ribbon which is either glued to each stick or threaded through pierced openings at the top of the sticks. The sticks are most often identically carved or pierced, creating a uniform ground or repeating pattern that can give the illusion of filigree or lace.

This collection features brisé fans, primarily English, from the early 19th century. All are rather small, with sticks between 6″ and 7″ long.

The earliest brisé fans came from China and Japan, and were exported to Europe in large quantities from the 17th century on.

Figure 3: Horn fan of identically pierced sticks, cut in a delicate lacy pattern. Sticks threaded with pink silk ribbon, and held together by an steel rivet. c.1790-1810.

European brisé fans, made in imitation of the delicate Chinese wooden and ivory fans but distinctly Western in style, were composed of thinly-sliced sticks of bone, horn, tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, or ivory that were often elaborately carved, gilded, and painted.

Sometimes plain, undecorated ivory sticks imported from China were completely painted in the style of a leaf fan. The East India Company imported large numbers of plain and carved brisé fans in ivory and tortoiseshell well into the 19th century, though later 19th century fans are much larger than these Regency examples.

Figure 4: Green horn fan of identically pierced sticks, alternately reversed to create a swag pattern. Hand painted with swags of flowers on both front and back. c1810-1820.

The brisé fan was popular in the 17th and early 18th centuries, but was never as widespread as the folding fan with a painted and pleated leaf. However, in the late 18th and early 19th century smaller fans had come into vogue, perhaps due to the narrower, high-waisted dresses that could no longer accommodate voluminous pockets beneath, where one could tuck a large fan. The smaller fan, often called “opera” size, could have easily slipped into a reticule. Whatever the reason, smaller fans saw an increase in popularity during the extended Regency period. There are several beautiful brisé fans from this period in the Royal collection, including examples with the Prince of Wales and other members of the royal family depicted on painted sections of pierced ivory sticks. This one shows the Duke of York.

Figure 5: Horn fan dyed in a faux tortoiseshell style. Identically pierced sticks, alternately reversed to create a swag pattern. Hand-painted with flowers on both front and back. c1800-1820.

Fans of this period, following the democratic ideals of the American and French revolutions, were also made more available to the general populace through cheaper materials – bone and horn instead of the more expensive ivory and tortoiseshell, and printed rather than painted leaves on folding fans. One of the reasons for the rise in popularity of the brisé fan during this period was that they were less labor-intensive, using identical sticks of a single pattern, created with a tiny jeweler’s saw, with little or no decoration. But the fashionable ladies of the ton carried brisé fans as well; their simplicity echoed the general simplicity of the neoclassical style of dress.

In the June 1813 issue of of La Belle Assemblée, it is noted in the General Observations on Fashion and Dress that “Ivory fans, with painted borders of flowers, are very much in request.” We can assume that the style of decoration shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5 are what is referred to, though on ivory fans. Or perhaps something similar to the ivory fan shown here. Two months later, the same magazine notes that “plain, small ivory fans promise to supersede the beautiful painted ones mentioned in our last issue,” and by the November 1813 issue it is reported that “plain ivory fans are universal.” By “plain” I do not believe they are referring to uncarved ivory, but rather unpainted pierced or carved ivory, as shown in Figure 1. Ackermann’s Repository of Arts also frequently mentions “carved ivory fans” in the descriptions of its fashion plates of the period, as in the detail of a print from 1813 shown in Figure 2. I believe that all such references to “carved ivory fans” can be understood to mean a brisé fan. In the print in Figure 2, it is clearly a brisé fan.

As fashion became more elaborate and fussy in the 1830s and beyond, the small, simple brisé fan became less popular, though some very elaborate brisé fans with neo-Gothic style sticks were made in the 1830s and 1840s. (See this example in the Victoria and Albert Museum.) Brisé style fans continue to be made, and are most commonly seen today in faux-ivory plastic fans.

Figure 6: Horn fan. The body of each stick is cut in a stack of round floral patterns, and each roundel is painted with blue and white enamel. c1800-1810.

The brisé fans of the early 19th century have an unmistakably Regency style in the carving that sets them apart from fans imported from the Far East. The same elements seen in Regency furniture, architecture, glasswork, ironwork, etc can be seen in the carved designs of brisé fans: delicate motifs and restrained elements from classical Greece and Rome, bolder forms drawn from ancient Egypt and Asia, and the rigid geometric order of neoclassicism.

Sometimes the carving and/or piercing is so delicate that it is decoration enough. (See Figure 1.) Most often, though, there is some painting of the sticks, frequently with simple swags of flowers, or other repetitive floral devices. (See Figures 3, 4, and 5.) It is not uncommon to have both sides of the fan painted, often with different designs. The fans with simple swags of flowers, for example, might have different types or colors of flowers painted on each side. Painting on brisé fans was more difficult than painting a fan leaf, even with simple painted designs of swags of flowers, and especially when there was a design on both sides of the sticks. The artist had to color each individual stick carefully so that the whole composition connected properly when the fan was opened.

All of the fans in this collection were purchased in England and are assumed to be English. Each are of a similar size, with sticks measuring 6 to 7 inches, the fully opened fan measuring approximately 12 inches. Figure 1 is made of ivory, the most popular material for fans of this period. Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6 are made of horn, with Figure 5 being dyed to resemble tortoiseshell. See a mother-of-pearl example here.

For more information on brisé fans, see the following sources:

- Hélène Alexander, The Fan Museum, Fan Museum Trust, 2001.

- Hélène Alexander, Fans, Shire Publications, 1995.

- Nancy Armstrong, A Collector’s History of Fans, Clarkson N. Potter Publishers, 1974.

- Anna G. Bennett, Fans in Fashion, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1981.

- Anna G. Bennett, Unfolding Beauty: The Art of the Fan, Thames & Hudson, 1988.

- Avril Hart and Emma Taylor, Fans, Victoria & Albert Publications, 1998.

- Alexander F. Tcherviakov, Fans, Parkstone Press, 1998.

In In the Thrill of the Night,

In In the Thrill of the Night, Wilhelmina gives each of the Merry Widows an ivory brisé fan before their first charity ball of the season, each fan painted with different flowers to match each lady’s dress.

In Once a Gentleman,

In Once a Gentleman, Prudence tries to flirt, without much success, using her ivory brisé fan.