Click on images to see larger versions.

As discussed in the article on Georgian Painted Silhouettes, the type of silhouette I collect is not the cut-paper type, but silhouettes that are painted. A painted silhouette provides a black profile of the sitter, just as the cut-paper versions, but painting allows for more detail in the hair and clothing. Silhouettes, which were called profile miniatures or shades, were painted on paper, plaster, and ivory, and reverse-painted on glass.

All but one of the pieces of jewelry selected for this article are painted on ivory, which was the most common medium for jewelry. The black pigment used was generally made of lamp black mixed with beer, though fine details were sometimes done with India ink. Bronzing – the technique of adding details in gold against the black – was done using either gold or bronze powder mixed with gum arabic.

Profile artists, or profilists, offered a cheaper and faster alternative to the fully painted portrait miniature, which was hugely popular during Georgian times. The sitter’s profile was typically traced using a pentagraph or other mechanism, which took only a few minutes. The sitter need not be present for the profilist to finish the work, painting in the profile and adding hair and fashion details. The original profile could be saved and used again to create additional framed profiles or to create smaller versions for jewlery. For example, if the original commission was for a single framed profile miniature, the sitter or his family might later want more copies, or perhaps smaller versions set into jewelry, especially for mourning pieces. If the original artist kept copies, as many did, he could simply use the original to produce more copies, even changing the original to update hair and fashion.

Silhouettes were set into all sorts of jewelry: rings, brooches, lockets, bracelets. They were very popular as mourning jewelry as they could be copied and sent to friends and family of the deceased – a much more personal memento than a mourning ring. Many of the pieces shown here, especially lockets, include locks of hair, which may mark them as mourning pieces. But as with all sentimental jewelry, unless there is a specific symbol or color of mourning, one can never be certain if a piece is a memento of mourning or a love token.

The most famous profilist of the Georgian period was John Miers, who worked from the early 1780s until his death in 1821. He worked strictly in black, ie no bronzing or colored details, and his delicate rendering of ruffles and lace and other fashion details is extraordinary. His most famous protégé was John Field, who came to work in Miers’ studio on the Strand in 1800 and stayed until Miers death, after which he set up his own studio. Field is best known for his bronzing details, which are extremely fine. All of the pieces shown here are either signed by or attributed to John Field during his tenure in the Miers studio, ie from 1800 to 1820. As you look at these images, be aware that they are much enlarged, and are in actuality VERY small, so all the details of hair and clothing, and even eyelashes, are quite tiny. Be sure to click on the images to see even larger versions.

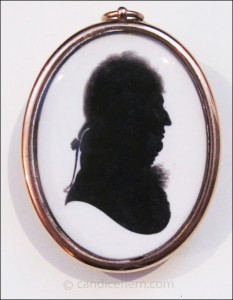

Figure 1 is a locket set in gold with a lovely braid of hair (presumably from the sitter) surrounding the profile. The profile, painted on ivory, is signed “Miers” in Field’s hand. The lack of bronzing places it early in Field’s career, probably before 1810. It measures 1″ x ¾”. The rendering of the neck ruff is especially fine. The addition of the braided hair marks this as a sentimental piece, but whether it was a love token or a mourning memento is not clear.

Figure 2 is a locket set in gold measuring 1¼” x 1″, containing a silhouette of a young woman painted on ivory, dating to c1815. From the studio of John Miers, it is signed “Miers” in the hand of John Field. The bronzed details of hair and even the earring is quite delicately rendered. The reverse of the locket contains a curl of brown hair under glass, presumably of the sitter. As there is also a narrow frame of black around the silhouette, this is no doubt a mourning piece.

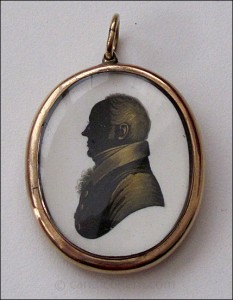

Figure 3 is also a locket set in gold, though much larger at 1¾” x 1¼”. The reverse is encased in glass, which would have held a lock of hair, though none is present. It is painted on ivory, and though unsigned, is attributed to Field. The interesting thing about this silhouette is that it came with a tiny handwritten note stuck to the back that says, “Robert Lowrie, killed in Peninsular War.” A bit of googling led me to Captain Robert Lowrie of the 91st Foot. He died on Oct 3, 1813 from a wound suffered in the Battle of the Pyrenees on July 28. He was 36. A tablet was erected to his memory in St. Martin’s Church, Lincoln (where he was born), by his brother officers as a mark of their esteem. Field’s skill, learned from Miers, is particularly evident in the shirt ruffle. If this is a mourning piece, then it is likely a copy of an earlier profile, based on the man’s hair styled in a long queue. Or it may simply be one of Fields’ earliest pieces, c1800.

Figure 4 is a small brooch set in gold, measuring 7/8″ x 5/8″, containing the profile of a woman painted on ivory, dating to c1810. It is signed “Miers” in Field’s hand, and shows his skill at bronzing, picking out details of hair, jewelry, and dress. Whenever bronzing was used, the face was always left in solid black, though ears, as here, or a man’s whiskers might be bronzed. There is a very narrow edging of black surrounding the silhouette, marking it as a mourning piece.

Figure 5 is a gold locket measuring 1″ x ¾”, containing the silhouette of a lady, from the studio of John Miers, unsigned, but attributed to John Field. It dates to c1820. This piece is unusual for both Miers and Field in that it is painted on paper. It is not typical to see bronzing done on paper, as the smooth surface of ivory lends itself to finer brushstrokes. But this example shows quite lovely bronzing. Woven hair of two shades, blond and brown, is set under glass on the reverse of the locket,. It was not unusual for the hair of both a husband and wife to be woven together in mourning pieces for one of the spouses, as may be the case here.

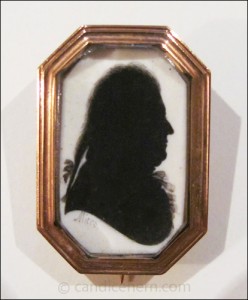

Figure 6 is another brooch, the smallest in my collection of silhouette jewelry at only 3/4″ x 1/2″. It contains the profile of a gentleman painted on ivory and set in an octagonal gold frame. Signed “Miers” in Field’s hand, it is likely another early piece, c1800, based on the man’s hair styled in a long queue. Once again, the neck ruffle is wonderfully painted, especially considered the size.

Figure 7 is a locket measuring 1″ x 3/4″, containing the silhouette of a gentleman, from the studio of John Miers, unsigned, but attributed to John Field. This piece dates to c1815. The bronzing is particularly fine. The reverse of the locket includes a lock of hair under glass, presumably from the gentleman in the painting, which, along with the thin edging of black surrounding the profile, suggests this is a mourning piece.

Figure 8 is another locket, measuring 1¼” x 1″, containing the profile of a woman painted on ivory and signed “Miers” in Field’s hand. It dates to c1815. The profile is edged in a much broader black border than the other pieces, leaving no doubt that it is a mourning piece. The glass case on the reverse is completely filled with braided blond hair, presumably from the deceased woman in the profile.

One of the reasons I collect painted silhouettes is that I find them more haunting than fully painted portrait miniatures. And as most of them are mourning pieces, it lends an additional level of poignancy to the profile portraits. I also never cease to be amazed at the level of detail that can be attained in simple black.

To learn more about painted silhouettes, see the following sources:

- Desmond Coke, The Art of Silhouette, Secker, 1913.

- E. Nevill Jackson, The History of Silhouettes, The Connoisseur, 1911.

- Arthur Mayne, British Profile Miniaturists, Boston Book and Art, 1970.

- Sue McKechnie, British Silhouette Artists and Their Work 1760-1860, Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

- David Piper, An Essay on English Portrait Silhouettes, Chilmark Press, 1970.

- Emma Rutherford, Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow, Rizzoli, 2009.

- Alice Van Leer Carrick, A History of American Silhouettes, Tuttle, 1968.

- John Woodiwiss, British Silhouettes, Country Life, 1965.