Portrait miniatures mounted as brooches, pendants, or lockets were very popular items of jewelry during the 18th century. Toward the end of the century, an unusual variation became fashionable: the eye brooch, or lover’s eye.

A lady’s blue eye painted in miniature on ivory, set in gold and surrounded by white sapphires. ¾” x ⅝” Late 18th century.

These were miniature portraits of the eye of a loved one. There is a great deal of controversy and confusion over how this fashion trend began, though almost all versions of the story involve the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and Mrs. Fitzherbert, his morganatic wife.

Most sources report the style was initiated when the famous miniaturist Richard Cosway painted the right eye of the Prince for a locket given to Mrs. Fitzherbert in November 1785, sent along with one of his many pleas for her to marry him.

A lady’s blue eye painted in miniature on ivory, in a gold eye-shaped setting. ½” x ¾” Early 19th century.

Earlier in 1785, however, Lady Eleanor Butler recorded in her diary the arrival of a young man who’d recently completed his Grand Tour, and who brought with him “an Eye, done in Paris and set in a ring — a true French idea.” That same year, Horace Walpole mentioned “portraits but of an eye” in a letter to the Countess of Ossory, saying, “A Frenchman is come over to paint eyes here.”

Whether the trend originated with the Prince at the time of his marriage to Mrs. Fitzherbert, or earlier in Paris, Prinny certainly was the first to popularize the trend in London. In any case, the intent was to keep the lover’s identity a bit of a secret by not revealing the whole face. Since the Prince was a leader of fashion, eye miniatures set as jewelry became very popular in the late 18th century through the early decades of the 19th century. It was a short-lived trend. By the 1820s, eye jewelry had gone out of fashion.

A gentleman’s brown eye painted in miniature on ivory, set in gold with black enamel and seed pearls. The combination of a black border and seed pearls (which can symbolize tears) marks this as a mourning brooch. ⅞” ⅝” Early 19th century.

It is likely that many eye miniatures were simply another variation of sentimental or mourning jewelry and had nothing to do with secret lovers. There are records from the miniaturist George Engleheart that show he was commissioned to paint eyes for entire families. This would explain, for example, female eyes mounted in very feminine settings, ie mothers giving eye miniatures to their daughters.

A gentleman’s brown eye painted in miniature on ivory, set in gold with garnets and seed pearls. Garnets often symbolize love and pearls can symbolize purity, so this is more likely a love token rather than a mourning piece. Early 19th century. 1″ x 1¼”

Eye brooches that have come down from the Victorian era were certainly sentimental or mourning pieces. Queen Victoria is said to have commissioned several as gifts, even though the notion of eye miniatures was by that time very old-fashioned. In Dickens’ Dombey and Son, published in 1848, the impoverished, aging spinster, Miss Tox, is described as wearing “round her neck the barrenest of lockets, representing a fishy old eye.”

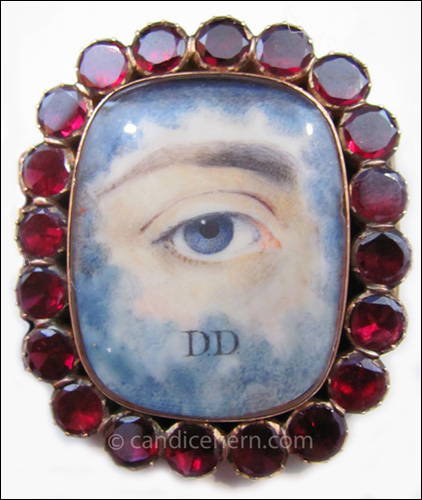

A gentleman’s blue eye painted on ivory, set in gold with garnets. Clouds surrounding the eye sometimes represent a deceased person gazing out from heaven. Initials DD likely belong to the sitter and not the artist. Early 19th century. 1¾” x 1½”

Though eye miniatures were most typically set in all types of jewelry — lockets, brooches, rings, watch fobs — they were also set in other objects as well, such as patch boxes and toothpick boxes. Some were painted on porcelain objects, such as teacups. All the lover’s eyes in this collection are set as brooches, and are assumed to be British. Please note their size, as the images are shown much larger than actual size. The first three, especially, are quite small.

Learn more about lover’s eyes from these sources:

- J. Anderson Black, The Story of Jewelry, William Morrow and Co., 1974.

- Graham C. Boettcher, editor, The Look of Love: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection, Birmingham Museum of Art, 2012.

- Shirley Bury, Jewellery, the International Era, Volume I: 1789-1861, Antique Collectors Club, 1991.

- Shirley Bury, Sentimental Jewellery, Stemmer House, 1985.

- Ginny Redington Dawes ad Olivia Collings, Georgian Jewellery 1714 – 1830, Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Hanneke Grootenboer, “Treasuring the Gaze: Eye Miniature Portraits and the Intimacy of Vision” in The Art Bulletin, Sept. 2006.

- Ann Louise Luthi, Sentimental Jewellery, Shire Publiations, 1998.

- Claire Phillips, Jewels and Jewellery, Victoria and Albert Publications, 2000.

- Diana Scarisbrick, Portrait Jewels, Thames & Hudson, 2011.

- Diana Scarisbrick, Jewellery in Britain 1066-1837, Michael Russel Ltd, 1994.

- George Charles Williamson, “Miniature Paintings of Eyes” in The Connoisseur, Sept-Dec 1904.