Click on images to see larger versions.

Charms and amulets have been used for centuries to protect the wearer against various ills and evils. In the middle ages there was the belief that certain stones had magical powers. Holy relics were set in jewels to protect the wearer. In the 16th century, memento mori (“remember that you must die”) jewelry became popular, decorated with skeletons, crossbones, coffins, and skulls.

By the 17th century, these same symbols were beginning to be used for jewelry no longer meant to warn of mortality but to commemorate the death of specific persons. The rapid growth of mourning jewelry at this time is attributed to the execution of Charles I in 1649. His followers wore his miniature portrait set in rings and lockets, sometimes worn secretly, and locks of his hair were much treasured.

The use of hair in sentimental jewelry is ubiquitous. Because hair survives time and decay, it has long been incorporated into tokens of affection as a sign that love outlasts death. In memorial pieces, bits of hair serve as a sort of shrine to the deceased. In the 16th and 17th centuries, locks of hair were enclosed in all sorts of precious and elaborate lockets, often hidden from view. In the 18th century, the lock of hair became a primary, and very visible, element of sentimental jewelry and was curled, plaited, and woven in decorative motifs, and sometimes was woven and knotted into bracelets, fob chains, and earrings. (The latter type became even more popular during the Victorian era.) Hair was also chopped up, macerated, or dissolved and used to paint miniature scenes of love and loss.

Morbid symbols of death, such as skeletons, skulls, and coffins continued to be used in English mourning jewelry well into the 18th century, but by the second half of the century had become less common and were replaced by images of sorrow. This reflects Enlightenment ideas in which expressions of grief and lamentation were accepted as a morally compassionate alternative to the 17th century emphasis on one’s own mortality.

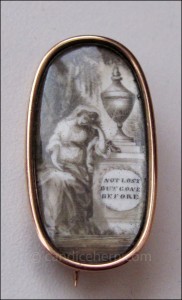

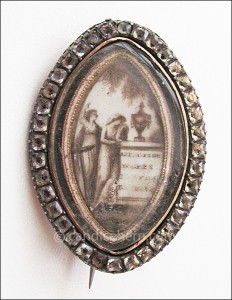

Throughout the late 18th century, sentiment, both sorrowful and romantic, began to be expressed in a more allegorical style with motifs like Cupid’s bow and arrows (love), flaming hearts or torches (passion, ardor), anchors (hope), entwined hearts (commitment), obelisks (fame), dogs (faithfulness, fidelity), weeping willows (sorrow), broken urns or columns (life cut short). These sentimental motifs were most often painted in miniature neo-classical scenes on ivory, frequently in sepia tones, and sometimes composed of bits of hair from the loved one commemorated. In Figure 1, are three stripes of hair at the bottom of the image, in three different colors. Perhaps from the children of the deceased? There are also bits of macerated hair in the depiction of the weeping willow branches in both Figures 1 and 2.

A sentimental inscription was often included on the image. Typical sentiments of grief, generally inscribed on a memorial urn or plinth, included, “Not lost, but gone before” (as seen on Figure 1), or “Weep not: it falls to rise again,” or “In death lamented as in life beloved;” or “Affection weeps, Heaven rejoices” (as on Figure 3).

Extremely popular during the last decades of the 18th century and the early 19th century, these pieces were set in brooches, pendants, rings, slides, bracelet clasps, and earrings. These miniature sepia paintings were produced in great numbers as tokens of love or expressions of sorrow, and though similar in style, no two were ever identical as each was hand painted. They would have been purchased ready-made, or commissioned from design books and sample cards. The pieces could be individualized with the simple addition of a name or initials, date of death, and age engraved on the reverse. Figure 2 is inscribed on the reverse: “Richard Davies, Ob 2 Feb 1772, Aged 49 years.” Occasionally the initials, or even the full name, of the deceased was added to the urn or column base in the painting. This indicates that the pieces were selected before being set in mounts. The mounts often incorporated additional sentiments — seed pearls signified tears, black enamel for mourning married persons, white enamel for mourning children and unmarried adults.

Familiar allegories and symbols of grief are shown in the brooches: a grieving widow (or mother) leaning sadly against an urn or plinth; a weeping willow; an anchor of hope. Figure 3 is pattern card of mourning symbolism. It shows two women beside a memorial urn atop a plinth with the inscription, “Affection weeps, Heaven rejoices.” One woman leans against the plinth in sorrow, the other woman points to the sky above, indicating the deceased has ascended into heaven. An anchor of hope stands in front of her. Tiny bits of hair are strewn at the base of the plinth, a ritual celebration of undying love for the deceased. (In memorials to spouses, it was common to include bits of hair from both the deceased and the surviving spouse at the base of the plinth, urn, or altar as a symbol of their bodies joined together for eternity.) Surrounding the painting are bands of black and white enamel. The white enamel suggests the death of a child or unmarried adult.

Figure 5 is an example of sentimental ambiguity. It could be a mourning piece, or it just as likely could be a love token. Many of the same symbols were used in both types of sentimental jewelry. On this large pendant, a woman offers a garland of flowers upon an altar to Hymen, the god of marriage, atop which a pair of hearts are aflame with passion. Above her, a figure of Cupid descends with a wreath of flowers, a motif representing the triumph of love. The altar includes an inscription, but is unreadable. The sepia figure is painted with bits of macerated hair, and both the garland and wreath also include bits of hair, presumably of the loved one. The tree and the low foliage are painted in reverse on the glass. The smile on the woman’s face most likely indicates she is celebrating love rather than grieving its loss, though all the romantic motifs can also be found in memorial pieces to deceased spouses. A famous miniature of Martha Washington in the collection of the Yale University Art Museum shows an allegorical memorial painting commemorating the death of George Washington on the reverse, and it includes two hearts joined on an altar to Hymen.

The little mourning tokens (Figures 1 through 4 are each approximately 1″ tall) continued in popularity throughout the Regency and for some years after. Victorian mourning jewelry became larger and more symbolic, with little scenes like the ones on these brooches replaced by single urns. anchors, etc. After the death of Prince Albert in 1861, Queen Victoria went into perpetual mourning for the rest of her life, bringing about a resurgence of mourning jewelry.

Sources for more information on Georgian sentimental jewelry:

- J. Anderson Black, The Story of Jewelry, William Morrow and Co., 1974.

- Shirley Bury, Jewellery, the International Era, Volume I: 1789-1861, Antique Collectors Club, 1991.

- Shirley Bury, Sentimental Jewellery, Stemmer House Publications, 1985.

- Mona Curran, Collecting Antique Jewellery, Emerson Books, 1963.

- Maureen DeLorne, Mourning Art and Jewelry, Schiffer, 2004.

- Robin Jaffe Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures, Yale University Press, 2000.

- Ann Louise Luthi , Sentimental Jewellery: Antique Jewels of Love and Sorrow , Shire Books, 1998.

- Geoffrey C. Munn, The Triumph of Love: Jewelry 1530-1930, Thames and Hudson, 1993.

- Clare Phillips, Jewelry, from Antiquity to Present, Thames and Hudson, 1996.

- Clare Phillips, Jewels and Jewellery, Victoria and Albert Publications, 2000.

- Diana Scarisbrick, Jewellery in Britain 1066-1837, Michael Russel Ltd, 1994.