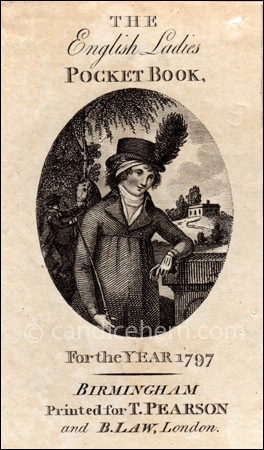

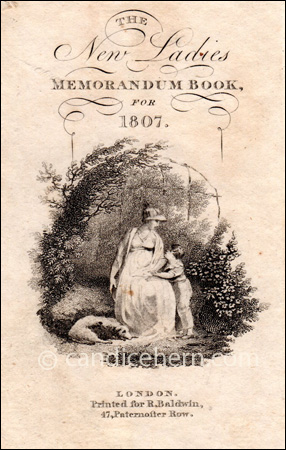

From the mid-18th century, small diaries or calendars for ladies were a common object found among the stock of almost all stationer-booksellers in Britain. They served the purpose of the pre-cell phone Day Timer, where you would note appointments in the calendar, keep track of expenses, and perhaps tuck inside other notes, lists, papers, or letters. Georgian ladies would keep their version of Day Timers in their pockets, and so they were often titled Pocket Books. But also Pocket Memorandums or Pocket Remembrancers or Pocket Companions.

“The English Ladies Pocket Book for the Year 1803,” published in Birmingham. Open to show the title page and the folded fashion print.

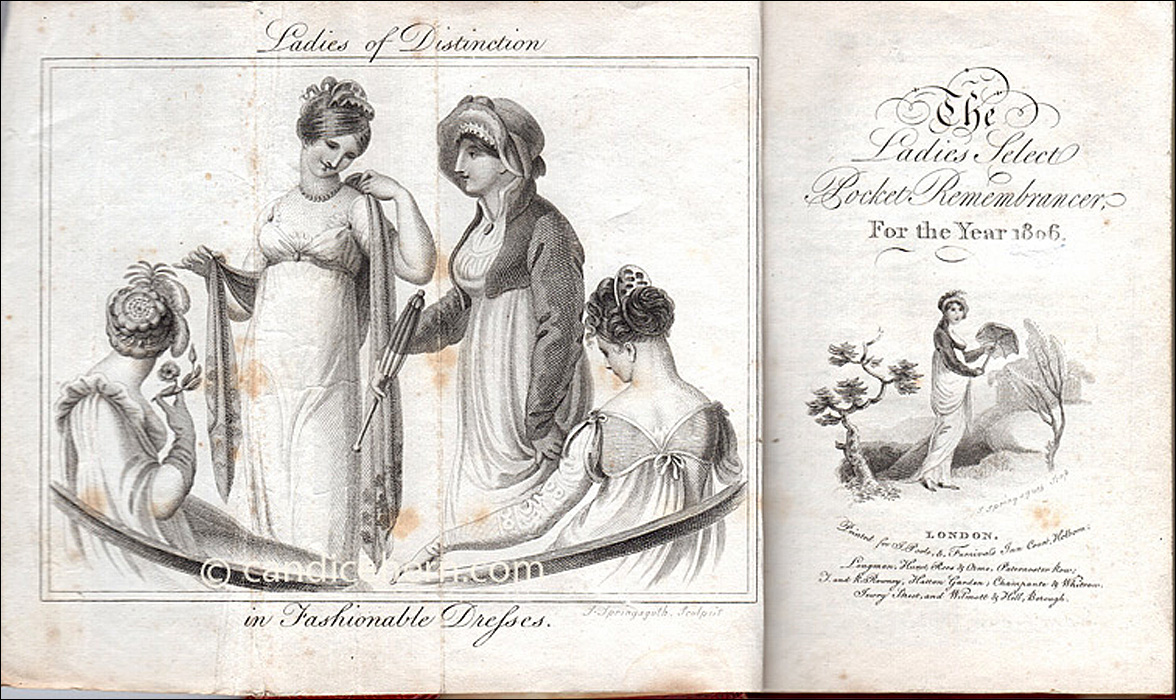

“The Ladies Select Pocket Remembrancer for the Year 1806” published in London, showing title page and fashion print frontispiece.

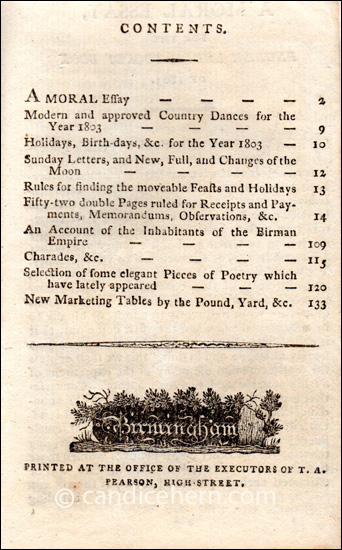

These Pocket Books were published throughout England by multiple publishers. Regardless of publisher, they had a standard format: a title page with an elegant engraving; a black-and-white fashion print, usually wider than the book pages and therefore folded (depending on the size of the print, sometimes double-folded, sometimes triple-folded); a year’s calendar, usually one page per week, with room to make notes on each day; a record of expenses, sometimes each week’s expense page placed opposite the calendar page, sometimes the annual expense record completely separate from the calendar; a page or pages titled Memorandum, left blank for making notes; and various amusements, such as essays, short stories, poetry, and games.

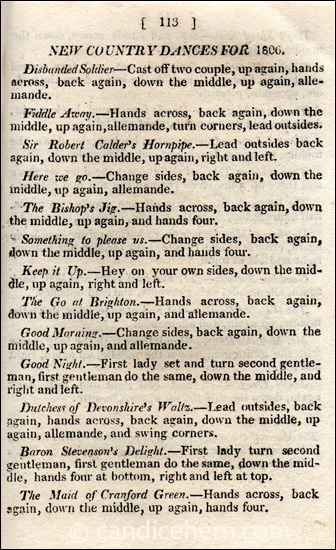

Some Pocket Books include such useful information as Hackney Coach fares, Watermen rates, Market Rates, and even how to calculate wages, ie for a servant. Some include a Table of Precedency Among Ladies. And some include the newest country dances.

From “The Ladies Select Pocket Remembrancer for the Year 1806” showing a page of New Country Dances for 1806.

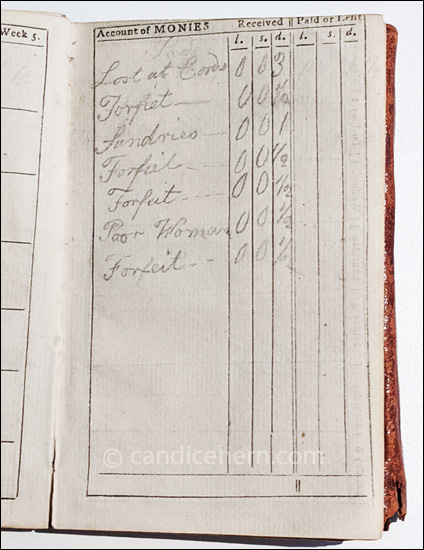

Apparently many ladies didn’t use their Pocket Books as intended. Sometimes, it was just a matter of having something to write in, and there are extant Pocket Books filled with hand-written recipes, to-do lists, and other things a lady might want to keep. My 1806 Pocket Remembrancer has no calendar or expense entries, but is filled with hand-written poetry. My 1803 Pocket Book has a few calendar and expense entries, but they cease by the end of January. A New Year’s resolution that didn’t last?

The typical size of Pocket Books seems to be about 3” by 5” in a leather binding with a flap or other closure to keep it intact. The front and back inside covers often had pockets where a lady could keep letters, calling cards, recipes, or bank notes. Inside the upper fold was often a pencil holder. One of my Pocket Books had tucked into one of the inside pockets a calling card for “Mrs. Peppercorne.” Was it the owner’s card? Or had she picked it up from the lady named?

Typical leather bindings for ladies’ Pocket Books. The top example has a flap that once had a button or snap to keep it closed. The bottom example has a flap that would have tucked inside a strap, now gone, to keep it closed.

Pocket Book open to show the pencil holder. Below the pencil holder is a pocket for cards or letters.

Pocket Books were typically printed in the late fall of the previous year, and were on sale by most stationers and booksellers before the end of the year. Advertisements suggest the cost of approximately 2 shillings.

When the new Regency narrow silhouette did not allow for pockets to be worn underneath the skirts – or at least not bulky pockets – the pocket diary would have been kept in a reticule. But they continued to be called Pocket Books throughout the 19th century.

Several publishers encouraged owners to retain their annual Pocket Books as a sort of autobiographical record, documenting their lives year-by-year. Some ladies did keep them. Elizabeth Shackleton kept 19 years worth of Pocket Books, with detailed diaries, from 1762 to 1781. Her Pocket Books were a significant source in Amanda Vickery’s book, The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England. But these little books are hard to find, so, unless families have kept Pocket Books closely held for generations, like those of Elizabeth Shackleton, I suspect not many ladies, or their families, actually kept them.