This collection is not, strictly speaking, from the Regency, but if you stretch the definition of the era into c1790, this type of purse would still have been in use. Once dresses took on the narrow silhouette we think of as Regency, ladies no longer wore pockets beneath their skirts, and these purses were no longer used.

During the 18th century, when women’s skirts were huge, they wore large pockets underneath in which they carried everything that would later be carried outside the dress in purses. The pocket gave its name to variety of accessories carried within it, including the pocket case. The term was used interchangeably with letter case and pocketbook to describe small envelope-style purses that would have been slipped inside a pocket.

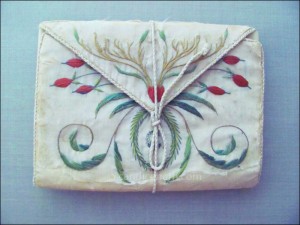

The pocket case was a small embroidered case, often made of silk, but also of linen, brocade, and leather. Though embroidery is the most common type of decoration, they were also decorated with crewel work or bead work. It was not uncommon to see the owner’s (or maker’s) name worked into the pattern of decoration. The cases are almost always lined, with silk or cotton or linen. They typically measure between 4 and 7 inches wide when closed. There is generally, but not always, a fold-over flap that kept it closed, sometimes tied or buttoned. Open, there were two sides with open pockets, sometimes multiple divided pockets, in which letters, bank notes, calling cards, diaries, squares of fabric for pins and needles, and other items would have been kept.

Pocket cases appear to have been made at home and not purchased ready-made. They were a popular aspect of domestic embroidery during the 18th century. Most often, they were made of silk embroidery, embellished with metallic threads, ribbons, cords, tassels, and spangles.

The earliest example in my collection is shown in Figure 1. Dating from c1750, it shows a bold floral pattern and, under the tie, the initial C. (Which is, of course, why I had to buy it!) Shown closed, the flap is tied with cord, which also binds the edges. Open, it includes two divided pockets.

Figures 2 and 3 show the same pocket case, from c1775, open and closed. Figure 2 shows the back when closed. The elegant embroidery includes a common sentimental theme incorporating Cupid’s bow, two arrows, a quiver of arrows, as well as a flaming torch of love. This device is often seen in sentimental jewelry. Because the theme here is clearly love, this may have been created for (or by) a bride. Figure 3 shows the case open. The arrangement of pockets here is typical of all the examples shown: two open pockets, with flaps over additional pockets. That is, behind each flap is a simple pocket, and underneath each flap is an additional pocket with expanding fan-folded sides, or a divided pocket creating two expanding spaces. So a purse like this would have at least 4 separate spaces to put items, or, with divided pockets, as many as 6 spaces. Not all pocket cases included insides flaps, as seen in Figure 3, but all those in my collection include two sides with single or divided expanding pockets.

Figure 4 shows the front, with flap, and back of a closed pocket case dating to c1780. The charming floral embroidery is framed in multi-colored cord. When opened, it has the same arrangement of pockets as seen in Figure 3. Whereas the other two pocket cases shown here are soft, this one is rigid, with the silk laid over firm cardboard.

Once the Regency silhouette brought about the end of the under-skirt pocket and introduced the reticule to replace it, these larger pocket cases disappeared. But the style remained in smaller card cases, which would have been carried in a reticule. Embroidered card cases were used throughout the Regency, Victorian, and Edwardian eras for calling cards.

Pocket cases of the type and size shown here were carried by both men and women through the end of the 18th century. Clearly each of these is meant for a female. Men’s pocket cases were more often made of leather or crewel work.

All of the pocket cases shown here were purchased in England and are believed to be English. Pocket cases were also popular in Europe, and especially in America.

Sources

- Vanda Foster, Bags and Purses, Batsford, 1982.

- Evelyn Haertig, Antique Combs and Purses, Gallery Graphics Press, 1983.

- Evelyn Haertig, More Beautiful Purses, Gallery Graphics Press, 1990

- Therle Hughes, English Domestic Needlework, Lutterworth Press, 1961.

- Clare Wilcox, Bags, V&A Publications, 1999.