The 18th century was a golden age for perfumes and perfume containers. Previous centuries had favored strong fragrances to mask the disagreeable odors of everyday life, and perfumes were usually made and dispensed by apothecaries. During the 18th century, more sophisticated scents found favor, especially delicate flowery fragrances, while the more voluptuous ambergris and civet-based scents fell out of fashion.

Figure 1: Bilston enamel case (3 1/2″ long) with brass fittings. Lead crystal glass bottle (2 3/4″ long) facet cut in honeycomb pattern with ground stopper. c. 1760.

Perfume producers flourished throughout Europe. The French court of Louis XV was known as la cour parfumée. London saw the rise of perfume shops such as those of Lillie and Perry and Bayley, many of them distinguished by signboards displaying civet cats, roses, and orange trees. Though still a luxury item, the rage for perfume became almost frantic, and it was often difficult for the producers to meet the demands, even with significantly expanded crops of perfume-making plants. Many new techniques and ingredients were developed during this period to satisfy the insatiable demand for perfume.

The rise of fashionable fragrance brought about new and equally fashionable ways to store it, display it, wear it, and use it. The finest porcelain factories produced bottles and flasks in every imaginable shape. Scent containers were also produced in glass, rock crystal, silver, gold, enamel, amber, ivory, alabaster, and many other materials.

Figure 2: Tortoise shell case (2 1/4″ tall) with sterling fittings; interior lined in red silk. Molded glass bottle (1 1/2″ tall) with ground stopper. c. 1780

Bottles were made to be displayed on a dressing table, to be tucked in a pocket, suspended from a chatelaine, or encased for traveling. Large traveling chests known as nécessaires contained everything a lady or gentleman would need during a journey, and these chests always included perfume flasks. The 18th century saw the proliferation of pocket-sized nécessaires, often called étuis, with miniature items, such as sewing kits, writing kits, and tiny toilettes that included scent vials. A perfume étui contains only bottles for perfume, and sometimes a tiny funnel for decanting.

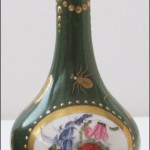

Figure 3: Bilston enamel case (2 1/2″ tall) with brass fittings. Bottle (2″ tall) of cut lead crystal with gilded brass top over a ground glass stopper. c. 1760

Perfume étuis were very tiny cases meant to fit in a pocket, or later in a reticule, but were also appropriate for display. They were generally hinged containers with one or more small bottles inside. They were produced in a greater variety of materials even than scent bottles, for materials not appropriate to hold perfume — for example, tortoise shell — could be used for the étui case, as in Figure 2.

Figure 4: Double case of shagreen (1 3/4″ tall) with sterling fittings; interior lined in red velvet. Two cut lead crystal bottles (1 1/2″ tall) with gold collars and ground stoppers. c. 1790

A very popular material for étuis was enamel. The most desirable enamel scent bottles and étuis were created in Bilston and Birmingham in England. (The Battersea enamel factory was only in operation from 1752 to 1755, and there is no evidence that any scent bottles or cases were made there.) The two Bilston examples in this collection, Figures 1 and 3, were made at the height of enamel craftsmanship, just after advances had been made that allowed enamel to be applied to a large surface without cracking during firing. Typically a perfumer or jeweler would purchase the plain metal cases, then send them to enamellists for decoration. Though extremely popular, they were nevertheless quite fragile, and it is a rare treat to find one today with little or no cracking or chipping.

Figure 5: Sterling case (1 3/4″ tall) made by Joseph Taylor, Birmingham. Interior lined in red velvet. Cut glass bottle (1 1/2″ tall) with cork stopper. Hallmarked 1801.

Another very popular material for étui cases was shagreen (Figures 4 and 6). The term comes from the Turkish saghri, meaning the croup of an animal. Shagreen is made from the skin of the shark, ray fish, or dog fish. It is ground flat so that the pearl-like papillae create a granulated pattern, and it is then dyed various colors, most often green. Shagreen was very fashionable during the 18th century and was often used for small portable cases, eg eyeglass cases or cosmetic cases. It found a resurgence of popularity in the early 20th century, with items such as cigarette cases. The étuis pictured are metal cases covered in shagreen, and the workmanship is so fine the shagreen seams are almost invisible.

Figure 6: Shagreen case (1 3/4″ tall) with brass fittings; lined in green paper and red velvet. Cut lead crystal bottle (1 1/2″ tall) with brass top over ground glass stopper. c1800.

Sterling silver was another popular material for étuis, and was produced by the same silversmiths, primarily from Birmingham, who specialized in small items advertised as “toys.” These were not toys as we know them, but a variety of small baubles and ornaments, such as vinaigrettes, patch boxes, nutmeg graters, snuff boxes, chatelaines, and étuis. Figure 5 shows a simple bright-cut decoration. The advantage of sterling, for the collector, is that the hallmarks allow for exact dating. This one is dated 1801.

These tiny étuis, encased in enamel or silver or shagreen or other materials, were small enough to be kept handy in a pocket or, later, a reticule. The case protected the liquid fragrance from spillage. This is perhaps the primary reason why they were developed.

Learn more about perfume Étuis from these sources:

- Linda Brine and Nancy Whitaker, Scent Bottles Through the Ages, published by the authors, 1998.

- Genevieve Cummins and Nerylla Taunton, Chatelaines, Antique Collectors Club, 1996.

- Kate Foster, Scent Bottles, The Connoisseur, 1966.

- G. Barnard Hughes, Small Antique Silverware, Bramhall House, 1957.

- William Kaufman, Perfume, Dutton, 1974.

- Edmund Launert, Scent and Scent Bottles, Barrie & Jenkins, 1974.

- Madeleine Marsh, Perfume Bottles, Miller’s, 1999.

- Heiner Meininghaus, Five Centuries of Scent and Elegant Flacons, Arnoldsche, 1998.

- Alexandra Walker, Scent Bottles, Shire Publications, 1996.