A distinctive equestrian costume for women, the riding habit, was first introduced in the 17th century.

They were tailored by men in the manner of men’s dress: a fitted jacket worn over a long skirt, often worn with a masculine hat. Samuel Pepys, ever helpful with observations of his time, wrote in 1666 of seeing the Queen’s ladies of honor “dressed in their riding garbs, with coats and doublets and deep skirts, just for all the world like men, and buttoned their doublets up to the breast, with periwigs and with hats; so that, only for a long petticoat dragging under the men’s coats, nobody could take them for women in any point whatever — which was an odd sight, and a sight which did not please me.”

Though the style and cut of riding habits changed with time and fashion, they continued to be tailored in a masculine style throughout the 17th and 18th centuries and into the early 19th century. In La Belle Assemblée in 1815, we read that: “Habits have, ever since they were first brought into fashion, been considered as decidedly calculated to give even the most delicate female a masculine appearance, and the wits of our grandmothers’ days were unmercifully severe on the waistcoat, cravat, and man’s hat which were then the indispensible appendages to a habit.”

Even after female dressmakers took on the task of designing and making women’s clothing around 1700 (male tailors had up until then made both male and female clothing), the riding habit continued to be made by men. It was not until the second decade of the 19th century that female dress-makers usurped this final bastion of the male tailor and began designing riding habits for ladies.

Included in this collection are a selection of fashion prints showing riding habits from 1799 through 1817. Be sure to click on the images to see larger versions and to read the original magazine text for all the English examples.

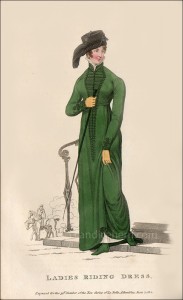

The riding habit of the Regency period generally consisted of a close-fitting jacket worn over a habit shirt, with a trained skirt. Sometimes the skirt and a bodice were joined in a single garment. (The bodice would have been made of plain cotton or muslin, as it was simply made to hold up the skirt, and was otherwise an undergarment.) Other times the skirt was a separate garment with a fitted waistband and straps over the shoulders, like suspenders.

Pocket slits in the skirts were not uncommon, as old-fashioned pockets were often worn under the habit (as riding made carrying a reticule difficult). In Figures 3 and 7 you can see the pocket holes which have been decorated to match the rest of the habit.

The habit skirt had a train that ensured the legs were completely (and modestly) covered when riding side saddle. There was usually a loop or tie of some kind inside the skirt to hold up the long train while walking. Skirts were made full, gathered or pleated in the back, typically with a small bustle beneath. The silhouette did not change during the first two decades of the 19th century, as did other garments, due to the required fullness of the skirt.

The habit jacket was basically a version of the spencer jacket. I suspect many were sometimes worn separately as spencers without the full habit. There is typically a short pleated peplum in the back, which is the Regency remnant of the tails in a man’s jacket, or in the female habits of the previous century, which closely copied male tailoring. You can see the peplum in Figures 1, 2 and 5. As Figure 1 is from 1799, the peplum is still somewhat long, especially as compared to the very short peplum in Figure 5 from 1815.

The habits of the first years of the 19th century still retained a tailored, masculine style, often adopting a military look, incorporating piping, braid, epaulettes, and frogging, in imitation of Hussar and other regimental uniforms. Ornamentation increased over the years, just as it did for other types of women’s fashion. This is clearly seen in the change from the plain cuffs on jackets (Figures 1, 2 and 3) to the embroidered cuffs of Figure 4, to the elaborate cuffs of the fabulous Glengary Habit in Figure 7.

The jacket and skirt were made of sturdy fabrics, most often some sort of wool, and, judging from the examples in fashion prints, were almost always either blue or green. No longer do we see the bright red habits of the previous century. A few French prints show gray or light brown habits, but I have never seen those colors in English prints, though the magazine description of the blue habit in Figure 3 says that “olive or puce are equally esteemed.”

Under the jacket, the habit shirt was generally made of muslin or cambric. They often followed the style of men’s shirts, with high standing collars, as in Figure 4, and a ruffled front. The shirt was tied beneath the bosom. Long sleeves might have lace cuffs to show beneath the jacket sleeves, though more often than not, the jacket cuff sat very low on the hand obscuring any shirt sleeves. The shirt might also be sleeveless. That style was sometimes called a chemisette and was worn to “fill in” the bodice of a day dress.

A cravat was sometimes tied around the high collar, as seen in Figures 6 and 7. The shirt became more frilly and feminine in the second decade of the 19th century, and ruffed collars were common, as seen in Figure 7. Figure 6 shows a combination of ruff and standing collar, with a blue cravat.

Hats also paid homage to male costume, as in the simple top hat shown in Figure 6 or the jockey bonnet in Figure 3, but often the hat was a very feminine counterpoint to the masculine tailoring of the habit. Hats worn with riding habits were not the typical capote or poke-style bonnet worn with other dresses. The hats shown in Figures 1, 4, 5, and 7 would not have been worn with any other sort of outfit, but were specially designed to be worn with the habit.

Note that in each of the fashion prints shown, the lady carries a riding crop, which was a required accessory. When riding side saddle, a lady needed the crop in her right hand to cue her horse, as she did not have a leg to do that on the right, as both legs were held on the left side of the saddle. In prints, the crop helped to easily identify a costume as a riding habit, since similar styles were used for carriage and traveling costumes. As a matter of fact, riding habits sometimes doubled as traveling costumes, as the sturdy fabric held up well over the dusty roads. The magazine commentary accompanying Figure 5 says the habit can be “happily adapted for travelling.” It is possible that a different skirt, without the long train, would be substituted for a long carriage ride.

Prints from the first decade of the century almost never mention the designer of the habit. But throughout the 1810s, more designers are specifically named. Figure 4 from 1812 cites “Mr. S. Clark of Golden Square.” But in most cases, a female dress-maker is mentioned, such as the ubiquitous Mrs. Bell. It is likely that as riding habits became more feminine and more elaborately ornamented that the male tailor no longer seemed the appropriate designer. Since female dress-makers had been tailoring short, close-fitting spencer jackets and pelisses for some years, it must not have been that great a leap to create a riding habit.

However, male tailors still offered their services to ladies who wanted habits, as evidenced in various advertisements in the ladies’ magazines of the day. Mr. G. Fox advertised in an 1817 issue of La Belle Assemblée: “Those Ladies who are very nice in their Dress are acquainted, that he employs particular workmen, who have for years constantly made up nothing but Woolen Pelisses and Habits, and therefore do form them into the most becoming and fashionable shapes, and much superior to any dress-maker.”

Sounds to me like a disgruntled man who did not appreciate women doing what had long been considered a man’s job.

For more information on fashion prints, see these sources:

- Alison Adburgham, Women in Print: Writing Women and Women’s Magazine from the Restoration to the Accession of Victoria, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1972.

- Irene Dancyger, A World of Women: An Illustrated History of Women’s Magazines 1700-1970, Gill and Macmillan, 1978.

- Jody Gayle, Fashions in the Era of Jane Austen, Publications of the Past, 2012.

- Madeleine Ginsburg, An Introduction to Fashion Illustration, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1980.

- Vyvyan Holland, Hand Coloured Fashion Plates 1770-1899, Batsford, 1955.

- Doris Langley Moore, Fashion Through Fashion Plates 1771-1970, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1971.

- Sacheverell Sitwell and Doris Langley Moore, Gallery of Fashion 1790-1822, Batsford, 1949.

- Cynthia L. White, Women’s Magazines 1693-1968, Michael Joseph, 1970.

For more information on riding habits, see these sources:

- Jane Ashelford, The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society 1500-1914, NAtional Trust, 1996.

- R. L. Shep, Federalist and Regency Costume: 1790-1819, Shep publications, 1998.

- Norah Waugh, The Cut of Women’s Clothes 1600-1930, Theatre Arts Books, 1968.