Click on images to see larger versions and to read more about the items.

This collection features a type of ceramic ware specific to the English Regency period. Bat-printed porcelains were produced primarily between 1800 and 1820. The process of decoration was complicated and somewhat difficult, and ultimately fell out of use. To understand how and why it was so different from most printed wares of the period, it is necessary to review the technology used to create transfer-printed ceramics.

Transfer-printing was a method of decorating ceramics by transferring ink, or colored pigment, from engraved copper plates to tissue-thin paper. It was developed in England in the 1750s and had an enormous impact on the manufacture of pottery and porcelain.

A flat copper plate was engraved with the desired pattern in the same way as the plates used to make paper engravings were produced. Once the plate was inked with a ceramic coloring, the design was impressed on a thin sheet of tissue-like paper. The inked tissue was then laid onto the item that had already been bisque-fired. It was then glazed, and fired again in a low-temperature kiln to fix the pattern. (Initially, the print was applied over the glaze, but since the ink tended wear off on overprinted pieces the underprinting method became more popular.)

Single-color transferware was made in blue, red, black, brown, mulberry, green, and (very rarely) yellow. Blue transferware was, and still is, the most desirable and collectible color. After 1840, mutli-colored printing was used, and sometimes transfer-printing was combined with hand-painting or enameling.

Transfer printing was developed as an affordable alternative to expensive hand-painted wares. Prior to the development of this technique, only the most affluent could afford complete dinnerware sets as every dish had been carefully hand-painted, a time-consuming and costly process. Now, hundred of sets of dinnerware could be produced in a fraction of the time for a fraction of the cost.

A more sophisticated method of over-glaze printing was employed for a short time in the early 19th century. Known as bat-printing, it was a complicated process using glue bats and powdered pigment that produced some very beautiful, delicately stippled wares, but which was almost completely abandoned by about 1820.

Cooper plates were still used to capture the design, but were stippled rather than line-engraved. That is, the entire design was made up of tiny dots, the dots being smaller or larger, closer or widely spaced, according to the depth of color required in the design. The copper plate was coated with linseed oil, then carefully “bossed” so that all the oil was removed, remaining only in the depressions of the tiny dots. Instead of tissue-thin paper, pads, or “bats,” of pliable glue and isinglass were applied to the copper plate. They were pressed gently to pick up the oil, then carefully removed and laid over a previously glazed ceramic piece, transferring the tiny dots of oil. Powdered pigment was then dusted onto the oil, creating the desired image. The result, after firing, was a very delicate, soft image that emulated the popular stippled engravings of Bartolozzi and others.

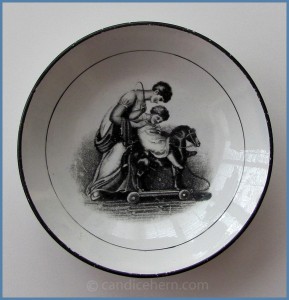

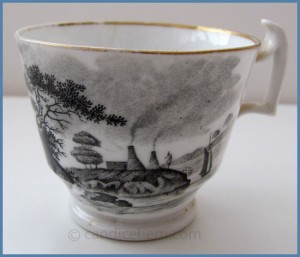

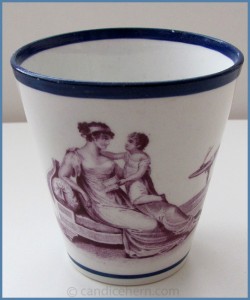

Copper plates for ceramics could now be very finely engraved since the plate no longer had to be charged with thick colored ink and no heat was required for the transfer. Soft, atmospheric landscapes could now be printed with great success (see Figure 2), as well as shells and fruits and flowers. Figural motifs of mothers and children in the style of artist Adam Buck were very popular bat-printed subjects (see Figures 1, 4, and 5), and often show lovely Regency details of fashion and furniture. (Which is why I have so many of them!)

Most often, the bat-printed scene or object decorated the central areas of the ceramic piece, which may also have been decorated with touches of gilt (see Figures 2, 3, and 4) or luster (see Figure 6) or bits of hand-painting. Underglaze blue and other colors were often used as borders (see Figure 5). The bat-printed scene was most often done in black, but occasionally in blue, purple, and orange as well (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 6 is unusual in that it represents a souvenir piece. In this case, it is a cup and saucer commemorating the death of Princess Charlotte in 1817. It is rather crudely printed — they were probably produced in a hurry — and though it is a fascinating bit of history, it is not a good example of bat-printing. Be sure to click on the image to see all the sentimental imagery in detail.

Bat-printing was a very precise operation, and so time-consuming that it somewhat defeated the mass production purpose of transfer-printing. The workman placing the bat on the ceramic piece did not have the advantage of a transparent paper transfer through which he could see before setting the design on the item. The transfer of the bat correctly required a good eye and a steady hand. The effort involved is no doubt one of the reasons the process was all but abandoned after 1820.

Here are a few selected references from among the vast literature on British pottery and porcelain:

- Paul Atterbury, editor, English Pottery and Porcelain: An Historical Survey, Universe Books, 1978.

- R. J. Charleston, editor, British Porcelain 1745-1850, Benn, 1965.

- Geoffrey A. Godden, British Pottery and Porcelain 1780-1850, A. S. Barnes and Company, Inc., 1963.

- Geoffrey A. Godden, An Illustrated Encyclopedia of British Pottery and Porcelain, Bonanza Book 1965.

- Geoffrey A. Godden, Godden’s Guide to English Porcelain, Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1992.

- W. B. Honey, English Pottery and Porcelain, A. & C. Black, 1962.

- Griselda Lewis, A Collector’s History of English Pottery, Viking Press, 1969.

- G. Wills, English Pottery and Porcelain, Guinness Signatures, 1968.