Regency Glossary

Over the years, readers have often written to ask Candice about the meaning of an unfamiliar term or phrase used in one of her books. Many of these terms are specific to late 18th and early 19th century England, and are often slang expressions or fashion terms. So, for those of you who may not be familiar with the language of the period, here is an illustrated glossary of terms and phrases Candice is most often asked about.

Click on any term to view full definition and sharing.

General · Slang · Women's Fashion · Gentlemen's Fashion

General Terms

abigail

A lady's maid

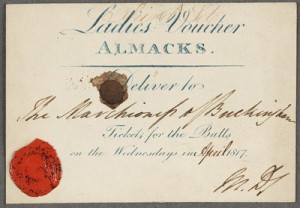

Almack’s

Assembly rooms on King Street in London. Private, very exclusive subscription balls were held there each Wednesday night of the Season. The annual subscription fee was 10 guineas, but only those who were approved by the lady patronesses were allowed to purchase subscriptions, or individual ball tickets. From 1765 to 1863. the committee of patronesses ruled supreme. In his memoirs, Captain Gronow wrote that the lady patronesses in 1814 were Lady Castlereigh, Lady Jersey, Lady Cowper, Lady Sefton, Mrs. Drummond-Burrell, Princess Esterhazy, and Countess Lieven. Other contemprary sources mention Lady Bathhurst and Lady Downshire. Captain Gronow called Almack’s “the seventh heaven of the fashionable world,” and said, “The gates were guarded by the lady patronesses whose smiles or frowns consigned men and women to happiness or despair.”

The Almack’s Voucher shown here is from the exhibit “Revisiting the Regency”, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, 2011. The voucher is assigned to the Marchioness of Buckingham. It is signed with the initials “M.D.”, which likely refers to Mary, Lady Downshire, one of the patronesses. This voucher is for balls in the month of April only, so apparently Lady Buckingham did not have an annual voucher.

apoplexy

A stroke.

banns

Public announcement in church of a proposed marriage. Before the banns could be read, there had to be a declaration of residency of four weeks by at least one of the parties, presented to the cleric at least 7 days prior to a public reading of the banns. The banns were read aloud during church service, following the reading of the second lesson, for three consecutive Sundays, with a query as to whether anyone knew of any reason why the couple should not wed. If one of the parties was from a different parish, the banns had to be read there as well. Once the banns had been read three times, without objection, the cleric issued a certificate and the couple was free to wed at a morning of their choosing in one of the churches where the banns had been read.

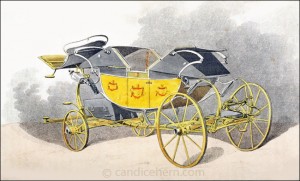

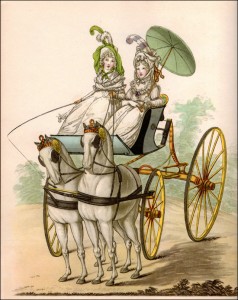

barouche

A four-wheeled carriage with two facing seats, the forward facing seat having a collapsible hood. It had a driver’s box seat in front and could be pulled by two or four horses. The barouche was the preferred carriage for aristocratic ladies (it was an expensive vehicle) during good weather when the hood could be pushed down.

The print, from Ackermann's Repository of Arts, January 1820, shows “A Barouche with Ackermann’s Patent Moveable Axles.”

batman

An orderly assigned to a military officer.

bluestocking

A woman with unfashionably intellectual and literary interests. The term is explained in Boswell’s “Life of Dr. Johnson”, as deriving from the name given to meetings held by certain ladies in the 18th century, for conversation with distinguished literary men. A frequent attendee was a Mr. Stillingfleet, who always wore his everyday blue worsted stockings because he could not afford silk stockings. He was so much distinguished for his conversational powers that his absence at any time was felt to be a great loss, and so it was often remarked, “We can do nothing without the blue stockings.” Admiral Boscawan, husband of one of the most successful hostesses of such gatherings, derisively dubbed them ‘The Blue Stocking Society’. Although both men and women, some of them eminent literary and learned figures of the day, attended these meetings, the term ‘bluestocking’ became attached exclusively, and often contemptuously, to women. This was partly because women were instrumental in organizing the evenings, but also because they were seen as encroaching on matters thought not to be their concern.

Bow Street Runner

The precursor of the metropolitan police, the Bow Street Runners were established in the mid-18th century by the magistrate of the Bow Street court, who happened to be the novelist Henry Fielding at that time. The runners were professional detectives who pursued felons across the country. They could also be hired by private individuals if the magistrate approved and could spare them.

cabriolet

A open-air owner-driven two-wheeled vehicle similar in appearance to a curricle except that is was designed for a single horse only, and instead of a seat in the back for the “tiger” there was only a small platform on which he would stand. It came into use about 1810, but reached its peak of popularity during the early Victorian years.

The painting shown is “William Massey-Stanley Driving His Cabriolet in Hyde Park” by John E. Ferneley, 1833. Yale Center fir British Art.

chariot

A traveling chariot was a small privately owned vehicle, the equivalent of the rented post chaise. See definition of Post Chaise for more details on this type of carriage.

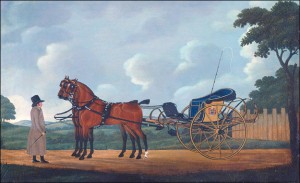

curricle

A fashionable open-air owner-driven two-wheeled sporting vehicle designed for a pair of horses and seating for no more than two (ie the Regency equivalent of a two-seater convertible sports car). There was a small seat in the rear for a groom or “tiger”.

The painting shown is “A Gentleman with His Pair of Bays Harnessed to a Curricle” by John Cordrey, 1806. Yale Center for British Art.

cut direct

A deliberate and public snub.

demi-monde

Literally “half world”; a class on the fringes of respectable Society. Often used in reference to courtesans, prostitutes, etc, though this is not strictly correct.

dowager

The widow of a peer, eg the Dowager Countess of Somewhere. The term was not added to a woman’s title unless and until the new (male) holder of the title married. For example, if the new Earl of Somewhere, the son of the late earl, is a young man when he inherits the title and has no wife, his mother continues to be styled Countess of Somewhere. When he marries, his wife takes that title and his mother becomes the Dowager Countess. The term is also sometimes used informally, and disparagingly, to refer to an older woman of the upper classes.

drum

A party.

Also, follow the drum, meaning to follow the army. For example, a woman who joins her soldier husband wherever he is posted is said to follow the drum.

entail

An inheritance of real property which cannot be sold by the owner but which passes by law to the owner’s heir upon his death. The purpose of an entail was to keep the land of a family intact in the main line of succession. The heir to an entailed estate could not sell the land, or bequeath it to anyone but his direct heir. Some entails were tied to a title and were defined in the original letters patent granting the title. The complications arising from entails were an important factor in the life of many of the upper classes, leaving many individuals wealthy in land but still heavily in debt.

foolscap

Writing paper. The term refers to the size of the paper (17 by 13½ inches, which was typically folded, and sometimes cut, in half ) and not the quality or weight. The standard foolscap size was in use since the 15th century, and the name derives from the watermark in the shape of a jester’s hat that was once used to identify it.

guinea

A gold coin worth 21 shillings. Last coinage in 1813.

hackney

A coach for hire. The Regency equivalent of a taxi-cab.

hell (ie gaming hell)

A gambling establishment. Typically not an elegant establishment, but rather a more disreputable, often secret, den of gaming. A young “pigeon” was more likely to fall victim to a dishonorable “shark” at a hell than at an elite gentleman’s club.

jarvey

Driver of a hackney coach.

jointure

A financial provision for a widow. Typically the amount is negotiated based on the portion she brought to the marriage, and is generally established as part of the marriage settlement.

laudanum

A tincture of opium used as a painkiller and sedative. A few drops were taken in a glass of wine or other beverage. It was widely used for a variety of ailments, by both adults and children. As with all opiates, it was potentially addictive.

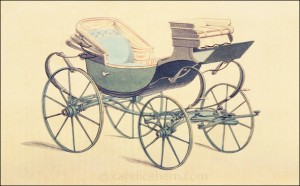

landau

A four-wheeled carriage with two facing seats, a driver’s seat in front, and two collapsible hoods that, when closed, joined in the middle to cover all occupants (except the driver). More often the hoods were folded back, and the vehicle was used as a barouche, ie for fashionable people to ride in and be seen. The landau was invented in Germany in the late 18th century. Though many references cite the first British landau as being built in the 1830s, the print shown here is from Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, February 1809, and is titled “Patent Landau.” The accompanying article says it was built by Messrs. Birch and Son, Great Queen Street, Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, and included “patented improvements in the construction of the roofs and upper quarters.”

linen draper

A fabric merchant.

Mayfair

The most desirable residential neighborhood in Regency London. Its unofficial boundaries are Picadilly on the south, Oxford on the north, Park Lane on the west, and Regent Street on the east. It includes Berkeley Square, Grosvenor Square, and Hanover Square.

phaeton

Any open-air four-wheeled sporting vehicle with seating for two is classified as a phaeton. Phaetons could accommodate one, two, or four horses. There were many variations of the phaeton. A popular version was the high-perch or highflyer phaeton, made fashionable by the Prince Regent. Its exaggerated elevation often made it dangerously unstable, which, naturally, made it popular among sportsmen.

The print, showing a high-perch phaeton, is from the magazine Gallery of Fashion, August 1794. (It's so high off the ground, one has to wonder how the ladies got up into it!)

pianoforte

An early incarnation of the piano, developed in about 1730. Keyboard instruments prior to that time could be played with precision but without variation of volume. The pianoforte allowed more versatility by producing notes at different volumes depending on the amount of force used to press the keys. It could be played softly (piano) or loudly (forte) — the full Italian term for the original instrument was gravicèmbalo col piano e forte (literally harpsichord with soft and loud).

The pianoforte shown is a Broadwood, 1791, from Kenwood House in London.

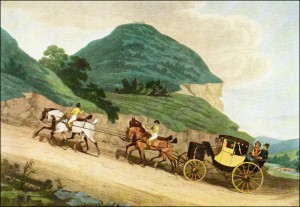

post chaise

The post chaise or traveling chariot was a small carriage pulled by two or four horses, and was owned or hired by those wishing to travel privately, that is not on a large public conveyance like a stage coach or mail coach. Hired post chaises were most often traveling chariots that had been discarded by gentlemen — sort of like a fleet of used rental cars. The hired chaises were generally painted yellow, hence the nickname Yellow Bounder. They were quite small, usually with only one forward seat facing a large glass window. There was often an outside bench seat in the back, over the rear wheel, where servants rode. Luggage was carried on a little forward platform between the front springs, and could also be strapped on the roof. The post chaise was “steered” by postilions, or post boys, seated upon the horses. There was no seat for a driver, and none was needed. One post boy was engaged to drive each pair of horses, ie a team of four horses was driven by two post boys, a lead-boy and a wheel-boy. Each rode on the left side of a pair, and wore iron guards on his right leg and foot to protect against injury from the center pole. The wheel-boy was generally the more experienced of the two. New post boys were trained by riding the lead team with the wheel-boy calling out instructions from behind. When the horses were changed along the route, new post boys were hired with them. Boys in name only, these riders were generally small, hardy little men, like jockeys, and were often colorful characters nattily dressed in “uniforms” associated with specific posting inns. They almost always wore white leather breeches and short jackets with large brass buttons, and tall beaver hats in which they kept their possessions. Private postilions were kept by those who traveled frequently and used their own traveling chariots. But these drivers often posted only to the first stop on a long journey, driving the owner’s team back home after new horses and post boys were hired.

The print shows a post chaise: “The Elected M.P. on His Way to the House of Commons” by James Pollard, 1817. From the book The Regency Road by N. C. Selway.

rake

This is a somewhat subjective term often used in historical romances to describe the hero. Webster defines a rake as “a dissolute person; a libertine” — in other words, not a very nice character. In romance novels, however, a rake seldom exhibits behavior that puts him beyond the pale. The term “rake” is most often used in the same way as “playboy” or “womanizer” but without the other implications of drinking, debauchery, and general lechery which inform the literal definition. A typical rakish hero will often have a number of women in his past, but the love of one special woman will cause him to give up the field forever, eg Jack in A Change of Heart or Tony in Once a Scoundrel.

rout

A crowded party, akin to a modern cocktail party. An American visitor to London in 1810 described it like this: “Great assemblies are called routs or parties … The house in which this takes place is frequently stripped from top to bottom; beds, drawers, and all but ornamental furniture is carried out of sight to make room for a crowd of well-dressed people, received at the door of the principal apartment by the mistress of the house, who smiles at every new comer with a look of acquaintance. Nobody sits; there is no conversation, no cards, no music; only elbowing, turning, and winding from room to room; then, at the end of a quarter of an hour, escaping to the hall door to wait for the carriage, spending more time upon the threshold among footmen than you had done above stairs with their masters. From this rout you drive to another where, after waiting your turn to arrive at the door, perhaps half an hour, the street being full of carriages, you alight, begin the same round, and end it in the same manner.”

Season

The social “Season” is generally described as beginning in early spring and lasting until the end of June. The season had some relation to the sitting of Parliament. It convened each January, so those involved in the government would head back to town at that time. No doubt their ladies spent the next couple of months updating their wardrobes and planning their social calendars for the spring. As for the term “Little Season”, supposedly in the fall — I have never seen any mention of a Little Season anywhere in a primary source. It is only referenced in books by Georgette Heyer and other writers of fiction. It makes sense that there might have been such a thing, as the upper classes who had left London for the seaside or the country might have returned to town in the fall, especially those involved in Parliament, which was still in session until November. But I have never come across the term Little Season anywhere outside of novels.

special license

A license obtained from the Archbishop of Canterbury or his office in Doctor’s Commons in London, that granted the right to marry at any convenient time or place. They were valid for 3 months. Without a special license, marriages could only take place between 8:00am and noon in a parish in which one of the parties has resided for a minimum of 4 weeks, and only after the banns had been read in that parish on three consecutive Sundays.

tiger

A liveried groom, generally small, generally young. An owner-driven curricle or phaeton typically had a groom’s seat between the springs on which the tiger sat. The single-horse cabriolet had a platform at the rear on which the tiger stood. He also managed the horses when his master ascended to or descended from the seat, and sometimes took the reins to exercise the horses while his master temporarily left the vehicle. A small, lightweight tiger was preferred in order to maintain the proper balance. In fact, it was something of a status symbol to have the smallest possible tiger.

The print shows a curricle with a tiger in the groom's seat. “The Marquis of Anglesey Driving his Curricle” – lithograph after Henry Graves. From the book The English Carriage by Hugh McCausland.

titles and forms of address

The British peerage, in order of precedence is:

duke/duchess: the Duke/Duchess of Somewhere, both addressed as Your Grace.

marquess/marchioness: the Marquess/Marchioness of Somewhere, addressed as Lord/Lady Somewhere. Note that sometimes the French form Marquis is used (though never the feminine French title of Marquise). Marquess is an older and purely English form.

earl/countess: the Earl/Countess [of] Titlename, addressed as Lord/Lady Titlename

viscount/viscountess: the Viscount/Viscountess [of] Titlename, addressed as Lord/Lady Titlename.

baron/baroness: Baron/Baroness Titlename, addressed as Lord/Lady Titlename.

The titles of duke and marquess are almost invariably territorial, eg Duke of Devonshire, Marquess of Salisbury, etc. The titles of earl, viscount, and baron are most often associated with a territory, eg Earl of Pembroke, but can also be based on a family name, in which case the "of" is dropped, eg Earl Spencer. A baron’s wife is not typically titled a baroness, though she is addressed as Lady Titlename. Only a woman who is a baroness in her own right uses that title.

The next two ranks are not peers, ie they do not sit in the House of Lords:

baronet: addressed as Sir Firstname, his wife as Lady Surname.

knight: addressed as Sir Firstname, his wife as Lady Surname; a knighted female is addressed as Dame Firstname, her husband as Mr. Surname, ie he does not share the distinction of his wife.

Whereas a baronet title is hereditary, a knighthood is not inherited.

For details on each rank as well as correct forms of address, these sites are recommended: http://www.debretts.com/forms-of-address/titles.aspx

http://laura.chinet.com//html/titles02.html

ton

Fashionable Society, or the fashion. From the French bon ton, meaning good form, ie good manners, good breeding, etc. A person could be a member of the ton, attend ton events, or be said to have good ton (or bad ton).

General · Slang · Women's Fashion · Gentlemen's Fashion

Slang Terms

affair of honor

A duel.

ape-leader

An old maid or spinster. An old English adage said that a spinster's punishment after death, for failing to procreate, would be to lead apes in hell.

at sixes and sevens

A state of confusion.

Banbury tale

A nonsensical story.

barking irons

Pistols.

barque of frailty

A prostitute.

bear leader

A traveling tutor.

blue ruin

Gin.

black books

To be in someone's black books means to be out of favor with him. For example, if a young man says he is in his father's black books, he means his father disapproves of him.

blunt

Money; ready cash.

caper merchant

Dancing instructor.

cent per cent

A usurer.

chit

A young girl.

cicisbeo

A married woman’s gallant, usually a platonic admirer.

cit

A contemptuous term for a member of the merchant class, one who works in or lives in the City of London, ie the central business area and financial center of London.

cock up one’s toes

To die.

come up to scratch

Make an offer of marriage. Diligent mamas are often hoping their daughters can bring a certain gentleman up to scratch.

corinthian

A fashionable man about town, generally a sportsman.

cyprian

A high-class prostitute,

dandy

A gentleman who is fastidious about his appearance, especially his clothing. He is not, as is often believed, a flashy or even flamboyant dresser, as was his 18th century predecessor, the Macaroni. George “Beau” Brummell epitomized the Dandy. He was concerned with perfect tailoring, the best quality fabrics, cleanliness, and simplicity of dress. He believed that good fashion should be understated and elegant, not eye-catching.

darken his daylights

To give [him] a black eye.

diamond of the first water

An exceptionally beautiful young woman. The phrase comes from a technical term used to describe diamonds. The degree of brilliance in a diamond is called its “water”, so a “diamond of the first water” is an exceptionally fine diamond.

dished up

Financially ruined.

doxy

Prostitute.

dun territory

In debt.

foxed

Drunk.

gull

(v.) to trick someone, generally to trick them out of money; or (n.) a simpleton, easily cheated.

handle the ribbons

To drive a coach or carriage.

high in the instep

Arrogant; snobbish; overly proud; and very much aware of social rank .

hoyden

A girl who is boisterous, carefree, or tomboyish in her behavior.

ladybird

A lover or kept mistress.

leg-shackled

Married.

light-skirt

Prostitute.

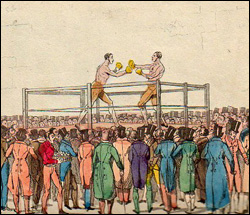

mill

A boxing match. The term can also be used to refer to a less formal bout, ie a barroom brawl or fist-fight.

The print shows a detail of "Fives Court: Tom and Bob Studying Real Life among the Millers" from Real Life in London, Volume 1, 1821.

missish

Squeamish, prim, prudish, ie behavior befitting a proper young miss.

mushroom

A person suddenly come into wealth; an upstart; an allusion to the fungus that starts up in the night.

nabob

An Englishman who made his fortune in India.

on dit

French phrase meaning, “It is said” or “One says”. In Regency slang, it meant gossip, eg “the latest on dit.”

on the shelf

Beyond marriageable age; no longer wanted. Used in reference to a spinster, never a man who, one assumes was always wanted, regardless of age.

parson’s mousetrap

Marriage.

Pink of the Ton

Also Pink of Fashion. The term is generally applied only to males and refers to a man at the height of fashion. A dandy. Per the 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: “the top of the mode.”

plant a facer

To hit someone in the face.

plump in the pocket

Wealthy.

Spanish coin

False flattery.

toad eater

Flatterer; toady.

under the hatches

Without funds; in debt.

vowels

An I.O.U.

watering pot

One who weeps too much and too often.

yard of tin

The horn, generally a yard or so long, used by the guard of a mail coach or stage coach to warn of approach and departure.

The print shown is a detail from "Quicksilver Royal Mail," painted by James Pollard, engraved by C. Hunt, published by Ackermann and Co., 1835. From the book The Regency Road by N. C. Selway. You can see the guard standing on he back of the coach, blowing his yard of tin.

General · Slang · Women's Fashion · Gentlemen's Fashion

Women's Fashion Terms

bandeau

From the French word for "strip," a bandeau is a narrow strip or band of (usually) stiffened fabric worn on the head to confine the hair, often with flowers, jewels, or feathers attached. It can also be a length of pearls or twisted fabric woven into the hair.

The print shown is a detail of "London Full Dresses", Fashions of London and Paris, June 1803: "Hair dressed and ornamented with a gold bandeau and flowers."

bombazine

A fabric with a warp of silk and weft of worsted, having a twilled appearance with a very dull finish. It was commonly dyed black, making it an ideal fabric for mourning garments.

brandebourgs

Frog-like fastenings, typically on a pelisse, which are traverse trimmings of cording and tassels in the military style.

The image shown is a detail of a "Parisian Walking Dress" from La Belle Assemblée, February 1818. This magazine always uses the spelling brandenbourgs.

busk

A flat length of wood, ivory, bone, whalebone, or steel used to stiffen the front of a bodice. Generally the busk was inserted into a busk sheath, or busk point, down the front of a corset. It was intended to keep the corset straight and upright, but also made it almost impossible to bend from the waist. Sometimes a busk was carved with emblems or romantic symbols and presented as a love token. Sailors, for example, often carved whale bone busks to give their sweethearts back home.

The busk shown has pricked decoration and inset colored paintings -- flowers, initials with hearts, and the date "July ye 20th 1796". Victoria and Albert Museum.

Brussels lace

A point lace with designs worked separately and applied to a net ground.

cambric

A very fine, delicate linen.

capote

A transitional form between a cap (soft, unstructured) and a bonnet (rigid, shaped). The brim is made of stiffened fabric, but the crown is of soft fabric shaped into a sort of pouch. The capote first made an appearance in the 1790s and continued throughout the 19th century, with the brim or poke becoming larger over time. It was meant for outdoor wear, though in the early years of the 19th century evening capotes were occasionally worn, though the brims would have been abbreviated.

The print is a detail from "Promenade Costume," Ackermann's Repository of Arts, September 1811.

capuchin

A cape with a hood.

capuchin collar

A roll collar following the V-neckline of a bodice.

Carthage Cymar

A scarf of silk or net, generally with a gold-embossed border. Typically worn with evening dress, attached to one shoulder and hanging long down the back.

You can see a Carthage Cymar here, in a fashion print from 1809.

chaplet

A garland or wreath of flowers worn on the head.

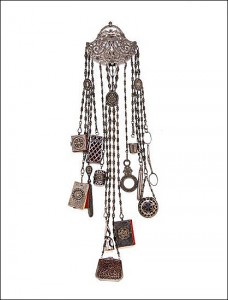

chatelaine

A set of decorative and useful items hung at the waist, recreating the concept of the medieval chatelaine or lady of the castle wearing her keys at her waist. Keys were still a part of a housekeeper’s utilitarian chatelaine, but they were also worn for strictly decorative purposes by fashionable ladies, and might include a watch and watch key, various etuis holding sewing or writing implements, vinaigrettes, pens, ivory leaves for notes, seals, and tiny coin purses. They were usually held at the waist with a chain, like a watch chain. Also referred to as waist-hung equipages. (Despite the Oxford English Dictionary implying that use of the term chatelaine for a fashion accessory is first recorded in 1851, there are several examples of the term in ladies’ magazines and trade cards of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.)

The cut-steel chatelaine shown, from the Victoria & Albert Museum, is French, early 19th century.

chemise

A loose-fitting, long, straight shirt with short sleeves worn under the corset as an undergarment. The term shift is also used for this garment, though it was considered a somewhat vulgar term.

chemisette

A short, sleeveless shirt, much like a dickey, used to fill in the neckline of a gown.

chip straw

Chip straw, used for bonnets, was not actually made of straw, but of thin pieces of wood. Chip could be plaited or woven just like straw but was sturdier, less flexible. Once formed into a sort of basket in whatever shape was currently fashionable, it could be bleached or colored, then trimmed with as desired.

Silk bonnets sometimes had chip and wire sewn into the seams, creating a framework to give them shape.

The image shown is a detail from "Promenade Dresses," Fashions of London and Paris, September 1804.

clocks

Fancy embroidery at the ankle of a stocking.

cornette

A day cap with a soft, rounded crown, tied under the chin. Almost always white, it was typically made of muslin, crepe, or other lightweight fabric, trimmed with lace and ribbons. It could be worn alone with indoor morning dress, or underneath a bonnet.

The print shown is a detail from a "Costume Parisien" print showing bonnets, from Journal des Dames et des Modes, April 30, 1812: "Cornette de Perkale."

dimity

A stout cotton fabric, plain or twilled, with a raised pattern on one side. Sometimes printed.

domino

A short hooded cloak with an attached mask, worn at masquerades. It was worn over evening attire by both men and women.

drawers

For women, drawers appeared c1800 in response to the sheer dress materials and closer-fitting narrow skirts. Lady Glenbevie’s journal records that the “modern and sporty” Princess Charlotte was wearing drawers in 1811. However, they were not generally adopted as a standard undergarment for another decade or more. Made of cotton or linen, early female drawers were made of two tubular pieces of fabric for the legs, attached to a deep waistband. They were laced at the back and tied with tapes, sometimes brought round to fasten with a button at the front. In later decades, they became long enough to been seen and were therefore more decorated.

epaulettes

Ornamental shoulder pieces, usually on outerwear such us spencers or pelisses. Later in the period also seen on dresses.

fichu

A length of fabric, usually triangular, worn around the neck and shoulders. Sometimes tucked inside the neckline of the bodice, sometimes crossed over the bodice. See the image at right in which all three women are wearing fichus of the late 18th century type. This “pouter pigeon” style of fichu fell out of fashion during the Regency years, though the term was resurrected c.1816 to refer to various sorts of bodice tuckers.

The print shows a detail of "Morning Dresses" from The Gallery of Fashion, July 1794.

fillet

A wire-stiffened string or braid of fabrics and/or pearls, twisted into an evening hairstyle. The fillet was a part of general passion for all things antique in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as fillets were often seen in Greek and Roman sculpture, frescoes, coins, and medallions.

The print shows a detail of "Evening Dress," La Belle Assemblée, October 1811: "A full turban fillet worn on the head."

flannels

A large flannel gown or wrap worn by bathers at the seaside or when taking the waters at a spa.

flounce

An ornamental row of decorative trim at the bottom of a skirt.

fly-fringe

A fringe of cord with knots and bunches of floss silk attached, used to decorate gowns.

French gores

Gores added into the skirt of a day dress to eliminate gathers at the waist. Introduced around 1807.

frock

A round gown (ie a dress where the bodice and skirt are a single piece) that closes in the back.

fustian

An inexpensive, coarsely textured cotton fabric with a linen warp.

gypsy hat

A flat-crowned, wide-brimmed straw hat with ribbons passing from the crown over the brim and tied in a bow under the chin or at the back of the neck.

The print shows a detail of "Garden Promenade Dresses," La Belle Assemblée, September 1809.

habit shirt

A short linen or muslin shirt, originally part of a riding costume, it was also worn to fill in a wide-necked bodice for day wear. Sometimes with a stand-up collar or ruff. Also called a chemisette.

half boots

Ankle high boots for women, typically for outdoor wear, often made of kid, but sometimes of sturdy cloth, such as jean or even velvet. They are flat-soled, and laced up the front or the side.

The half boots shown here are from the Victoria & Albert Museum, c1815-1820.

half dress

Something worn at informal evenings. Dressy, but not as formal as full-dress.

See the Overview of Half Dress in the Fashion Prints section for a more comprehensive description.

Huguenot lace

An imitation lace with a muslin net ground on which floral cut-out designs were sewn.

India muslin

A soft, opaque, silkier blend of cotton muslin.

jaconet

A thin cotton fabric, with a texture between muslin and cambric.

jockey cap

This style of cap or bonnet was very popular through about 1813. It is basically a capote in style, with the crown fitting a bit closer to the head, in the manner of a jockey's racing hat.

The jockey cap shown here is from a "Costume Parisien" print in the French magazine Journal de Dames et des Mode, November 1800.

lappets

Two long strips of material, most often lace, that hang from the top of the head down the back or over the shoulders. They can be extensions of a cap band or any sort of headdress. Lappets were a required element of female court dress from the early 18th through the early 20th centuries.

The print shows a detail from "Costume de Présentation" from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, July 31, 1814. After the restoration of the Bourbon family to the monarchy in 1814, French court dresses seen in prints show many of the same elements of English court dress, including lappets.

leghorn

A fine plaited straw, made from an Italian variety of wheat that has been dried and bleached. The name specifically refers to the type of straw, and not the shape of the hat, as is often incorrectly assumed.

leno

A transparent gauze-like fabric of linen thread.

Limerick gloves

Often referred to as “chicken skin” gloves, they were actually made from the tanned skins of unborn calves. They were usually cream or yellow in color and were much sought after for their tight fit due to the extremely thin skin.

lutestring

A very fine, corded glossy silk.

mantle

A cloak. In cooler months, it is typically 3/4 or full length. In warmer months, it can be quite short.

Mechlin lace

A bobbin lace, with a fine twisted-and-plaited, hexagonal net ground, the pattern outlined with a loosely spun silk cord. Best known for its floral patterns

mitts

Also called mittens. Gloves with open fingers and thumbs. Though gloves were removed during meals, mitts could be worn for informal meals like tea.

mob cap

A mob cap, which dated back to the early 18th century, was typically a white indoor cap made of cambric or muslin, with a puffed crown that covered the entire head, trimmed with lace and ribbon. It was most often tied under the chin. During the Regency years, the crown was less puffed and worn closer to the head.

The print shown is a detail of "Morning Dress" from Ackermann's Repository of Arts, May 1813: "The Brunswick mob cap, composed of net and Brussels lace."

modiste

A dress-maker or fashion designer. Always female.

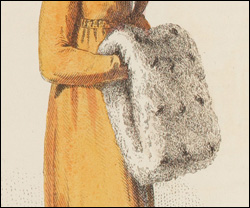

muff

A covering for both hands as a protection against cold, also used simply as an elegant accessory. Muffs were generally tubular, and made of fur, feathers, padded silk, and various other materials.They varied in size, sometimes reaching enormous proportions.

The print shows a detail from "Promenade Dress," Ackermann's Repository of Arts, January 1814: "White spotted ermine or Chinchilli muff."

muslin

A fine, semi-transparent cotton fabric. It could be plain, patterned, or printed.

pattens

Ladies footwear for inclement weather, worn over a normal shoe, to elevate her a couple of inches above the mud or slush or rain puddles. The raised patten was made of wood or metal, held in place by heather or cloth bands.

The image shows a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, December 15, 1811. You can see the normal shoe has been slipped into a leather patten raised on a metal ring.

pelerine

A cape-like collar, that typically just covers the shoulders. They became more popular beginning in the 1830s, but did appear in the earlier decades of the century.

The print shown is a detail from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, July 31, 1818.

pelisse

An outdoor coat-like garment worn over a dress, with or without sleeves, made of a variety of fabrics and linings, depending on the season and the occasion. Until around 1810, the pelisse was generally ¾-length. After that time, it was almost always ankle-length.

A flat, slitted pouch or bag worn beneath the dress, tied around the waist with tapes. Generally about 12″ or more long. They were accessed via a pocket slit in the side seam of a skirt. Common during the 18th century before reticules (purses) came into popularity, pockets fell out of use when the skirts narrowed during the Regency. However, muslin gowns c1805 in the collection of the Museum of Costume in Bath include pocket slits, so they did continue in use for the early years of the new century, but must have been reduced in size to avoid a bulky look.

The pocket shown here is an 18th century linen pocket from the Museum of Costume in Bath.

quilling

Small round pleats made in lace, tulle, or ribbon lightly sewn down, the edge of the trimming left in open flute-like folds. Used for trimming dresses and bonnets.

quizzing glass

A monocle or small magnifying glass dangling from a neck chain or ribbon, worn as a fashionable accessory by both men and women.

See examples of quizzing glasses from Candice's collection here.

reticule

A lady’s purse. More properly called a ridicule, probably because it seemed a ridiculous notion in the late 18th/early 19th century to carry outside the dress those personal belongings formerly kept in large pockets beneath the dress. When waists rose and skirts narrowed, bulky pockets could no longer be accommodated without spoiling the line of the dress, and so the ridicule became an essential accessory. The term “reticule” seems to have come into use around the mid-19th century. It is used often in Candice’s books as the more familiar, if less accurate, term.

The image shows a detail from a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, December 26, 1801: "a ridicule of scalloped-edged tulle."

round gown

A dress with the bodice and skirt joined in a single garment (during the Regency and earlier, these pieces were generally separate), with the skirt closed all around, ie not opened to expose an underskirt.

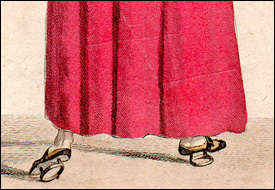

sandals

Slippers cut low over the foot and tied on by a criss-cross of ribbons or strings over the instep and around the ankle. They were not the open-toe summer show we know as sandals today. Any shoe that laced up the ankle was called a sandal.

The print shown is a detail from "Ball Dress," Ackermann's Repository of Arts, April 1811: "White satin sandal-slippers, tied with green ribbon round the ankle."

sarsnet

A thin twilled fabric which uses different colors in the warp and weft, thus allowing the fabric to subtly change colors as it moves. Though it is sometimes spelled sarsenet or sarcenet, the fashion magazines of the Regency period almost always use the spelling sarsnet.

spencer

A short, waist-length jacket (ie following the high waist of the current fashions, not the natural waist), with or without sleeves. Generally an outdoor garment worn in the morning or afternoon, but could also be part of an evening ensemble, when it was most often sleeveless. The spencer was adapted from a short, double-breasted men’s jacket, without tails, that was named for the 2nd Earl Spencer, who is said to have started the fashion in the 1790s.

The print shown is a detail of "Parisian Home Costume" from La Belle Assemblée, July 1817.

stays

A corset. Stays was the more commonly used term through the end of the 18th century, when he French term "corset" began to be used. Both terms were in common use during the Regency.

Stays of the Regency era were typically long, reaching the hip bones, with shoulder straps and a busk in front. They are most often made of linen or cotton, lightly boned for additional stiffness, and laced up the back. Shorter corsets were also worn during the Regency, but the long corset seems to have been the most popular, as it helped to smooth the line of the vertical silhouette.

The early 19th century stays shown are from the Kyoto Costume Institute.

stuff

A general term for ordinary wool.

tiffany

A transparent silk gauze.

tippet

An abbreviated cape. Similar to what might today be called a stole or a boa. In the late 18th century they were long and slender, in the form of a modern boa. By the mid-Regency, they had become a sort of capelet.

The print shows a detail from "Morning & Walking Dress," Ackermann's Repository of Arts, November 1810. It is described as a "French tippet of leopard silk shag."

toque

A close-fitting turban-like hat without a brim, worn with both day and evening wear. Became fashionable in late 1816 and beyond.

The print shown is a detail of "Walking Dress" from Ackermann's Repository of Arts, June 1818: "Head-dress, a pea-green satin toque, ornamented with flowers."

tucker

A white edging of lace, lawn, or muslin, usually frilled, on a low neckline. A tucker was often worn for modesty during the daytime on a low-cut dress that might be worn without it during the evening, When it was turned over to hang down over the front of the bodice, it was called a "falling tucker."

undress

A term used for simple, casual gowns for wear at home.

vandyke

Named after the painter Anthony Van Dyke (1599-1641), a style of collar or trimming with a dentate (ie sawtooth) border in lace or fabric.

General · Slang · Women's Fashion · Gentlemen's Fashion

Gentlemen's Fashion Terms

banyan

A loose-skirted coat worn by men as a dressing gown. They were typically worn over a shirt, waistcoat, and breeches or pantaloons, ie the gentleman would be dressed in all but his coat. The banyan would be worn while having breakfast alone, and when receiving morning visits from male friends. Though there was a brief period in the mid-18th century when it was fashionable to wear an elegant banyan in public, for the most part, a banyan was only worn in the privacy of one's home.

The banyans shown here are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, British c1780, when banyans of very costly materials were de rigeur.

beaver

Man’s black top hat made of felted beaver wool.

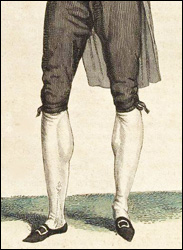

breeches

Worn for both evening wear and day wear. For riding, sport or country attire, they might be made of leather or buckskin, and were more or less the equivalent of a pair of jeans. For evening, or for formal servants’ livery, they might be made of satin. The front of the breeches opened with a flap called a “fall” that buttoned at the hips. Breeches fastened at the knee, or just below the knee, with either buttons, ties, or buckles. During the Regency, breeches were generally high-waisted and full at the hips. (Ladies would be unlikely to ogle a gentleman’s bottom while he wore breeches. They were not tight-fitting enough to be interesting.) By the late Regency, pantaloons had almost completely replaced breeches for day wear when boots were worn. Breeches continued to be worn for very formal evening occasions until the 1820s when trousers replaced breeches for full dress. Breeches also continued to be a requirement of gentlemen's court dress throughout the 19th century.

The image is a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal de Dames et des Modes, August 18, 1803, showing striped breeches.

cravat

A large square of lawn, muslin, or silk — often starched — folded into a long, narrow tie, worn around the neck with the ends tied in a bow or knot in the front.

facings

Material of a different color that shows when the cuffs and collar are folded over. In the military, different colored facings implied different regiments.

fall

A flap to the front of breeches, pantaloons, and trousers that buttoned up to the waistband, at the hips.

frock coat

A single-breasted tail-coat with full shoulders, tight sleeves, and fitted body. Gained popularity during the late Regency.

greatcoat

A man’s overcoat, typically with multiple capes at the shoulder, reaching at least the knees and sometimes long enough to almost touch the ground. The capes could hang long, as in the image shown here, or shorter, just below the shoulders. The number of capes could range from two to as many as ten, and were removable. The greatcoat was typically made of wool, and was most often worn for driving, or for walking in inclement weather.

The image shown is a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, March 31, 1811. The extra long sleeves are a French affectation.

Hessians

A style of man’s riding boot that is calf-length in the back and curves up in front to a point just below the knee, from which point hangs a tassel. Generally made of black leather, they sometimes had a narrow border at the top in a different color, eg white-topped Hessians. Certain dandies sometimes wore gold-tasseled Hessians. Beau Brummel is said to have kept his black Hessians gleaming by using a special boot polish made of champagne.

The image shows a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from Journal des Dames et des Modes, May 25, 1809, where the gentleman is wearing knitted pantaloons with Hessian boots.

kerseymere

A fine, twilled, closely-woven wool often used for breeches.

lawn

A very fine semi-transparent linen cloth, often used for men's shirts.

nankeen

A corruption of “Nanking.” A yellowish brown sturdy cotton fabric used for men’s work breeches or children’s play clothes.

pantaloons

In reference to male fashion, pantaloons are close-fitting tights or leggings that were introduced during the 1790s. They were often called "inexpressibles" as they were quite revealing, leaving very little to the imagination. They ended just below the calf, where button fastenings or straps kept them in place. In the latter years of the Regency, they reached the ankles. Pantaloons had a waist band, with a back vent and a front “fall”. They were generally made of knitted fabric to achieve the close fit. Pantaloons were typically worn with boots.

The image shows a detail of a "Incroyable: chapeau à la Robinson" from Incroyables et Merveilleuses, 1815. The gentleman is wearing very tight pantaloons and Hessian boots.

quizzing glass

A monocle or small magnifying glass dangling from a neck chain or ribbon, worn as a fashionable accessory by both men and women.

See examples of quizzing glasses from Candice's collection here.

spurs

Worn with boots by men of fashion for all occasions when boots were appropriate, even when not riding.

stock

A shaped neckband of stiffened material or horsehair, covered with fabric, worn high at the throat, and fastened at the back with ties or buckles. A neckcloth or cravat was typically worn over the stock. A stock, often in black, was a part of most military officers’ uniforms.

superfine

A high quality broadcloth, made of merino wool, heavily felted, raised, and cropped to provide a slight lustrous sheen. Much used for men's coats throughout the 19th century.

tail coat

A double-breasted coat, cut to form tails at the back while the front was cutaway at the waist. The collar was generally stiff and high-standing with notched lapels. This was standard men’s wear during the Regency, with changes over time in the cut of the waist (straight or curved), the width and notching of the lapels, the fullness of the sleeve, etc.

The image shows a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from Journal des Dames et des Modes, May 25, 1809. The straight-cut waist was by then more popular than the curved cut of earlier years.

toilinet

A fabric blended of cotton, silk, and wool. The warp was of cotton and/or silk, the weft of wool. It was extremely popular for waistcoats during the Regency.

top boots

Sometimes called tall boots, as they road higher on the calf, top boots had turned-down tops, often in a lighter color than the boot, and low square heels. Loops on each side of the boot facilitated pulling them on. Boot garters were sometimes attached to the back of the boot and fastened in front, above the boot, as seen in the print shown here. Top boots were usually worn with pantaloons or breeches.

The image shows a detail from a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, December 20, 1811. Dressed for riding, the gentleman is wearing top boots with boot garters and spurs.

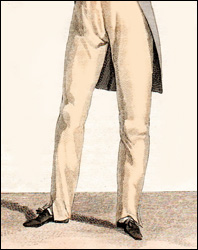

trousers

During the Regency period, trousers were basically a type of pantaloon that reached the ankle. They were not as tight-fitting, but instead fell almost straight from hip to below the ankle. Beau Brummell is said to have invented the fashion for wearing black trousers for evening wear, with straps under the foot to keep the trouser line straight. If straps were not worn, often there is a slit at the hem in the front, as shown in the print, allowing a long trouser leg without a break, or bunching up, in the front over the shoe. Trousers were worn with simple shoes or pumps, never with boots.

The image hows a detail of a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, June 25, 1812.

unmentionables

A euphemism for men’s breeches or trousers.

waistcoat

A sleeveless under-coat (what Americans would call a vest), either single or double breasted. During the Regency, they were short, and cut square across the waist. The single-breasted waistcoat was most often worn with evening wear; single- or double-breasted styles were worn with day wear. Throughout the early 19th century, the waistcoat almost always had lapels. Sometimes waistcoats were layered, often pairing a white waistcoat underneath a patterned waistcoat.

The image shown is a detail from a "Costume Parisien" print from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Mode, December 20, 1811.

watch fob

A short chain or ribbon with an attached medallion or ornament that connected to a man’s pocket watch and hung from a small pocket in his waistcoat. Men often wore several fobs, along with seals and other ornaments, clustered together on a single chain or ribbon.

The print shows a detail of "Concert Dresses" from Le Beau Monde, September 1807, where the gentleman is wearing two fobs on a gold chain.