Behind the Scenes

for

for

The Bride Sale

One of my favorite aspects of writing historical romance is the research. As so often happens, the idea for this story was born out of an interesting detail uncovered while researching another book. I was intrigued by a short article I came across in the London newspaper, the Morning Chronicle from July 15, 1814. Entitled “The Smithfield Bargain,” it read as follows:

“One of those scenes which occasionally disgrace even Smithfield, took place there about five o’clock on Friday evening (July 14th), namely — a man exposing his wife for sale. Hitherto we have only seen those moving in the lowest classes of society thus degrading themselves, but the present exhibition was attended with some novel circumstances. The parties, buyer and seller, were persons of property; the lady (the object of sale), young, beautiful, and elegantly dressed, was brought to market in a coach, and exposed to the view of her purchaser, with a silk halter round her shoulders, which were covered with a rich white lace veil. The price demanded for her, in the first instance, was eighty guineas, but that finally agreed upon was fifty guineas and a valuable horse upon which the purchaser was mounted. The sale and delivery being complete, the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go. The purchaser in the present case is a celebrated horsedealer in town, and the seller, a grazier of cattle, residing about six miles from London.”

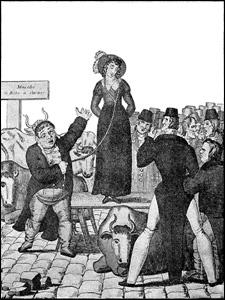

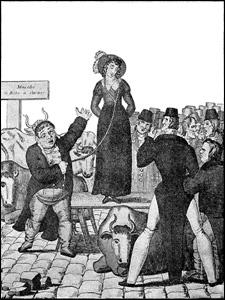

French print c1820

Further research led me to discover that wife-selling occurred more often in Britain than I had imagined. It was most prevalent among the lower classes, where the cost of a Parliamentary divorce was prohibitive. (A couple could dissolve a marriage in the ecclesiastical courts, which allowed them to separate but not to re-marry. Only an Act of Parliament could legally dissolve a marriage, until 1858 when divorce became legal. Even then, however, it was an expensive legal process that most of the working classes could not afford.) Wife sales, though never commonplace, were seen as an unofficial alternative to divorce. For reasons unclear to me, wife sales were primarily concentrated in areas of Cornwall and Devon. Lawrence Stone in his book Road To Divorce reports the numbers of recorded wife sales grew from two per decade in the mid 18th century to fifty per decade in the 1820s and 1830s. These statistics, however, only represent those wife sales that were recorded in newspapers. One might assume that many more went unrecorded.

There were certain rituals involved in a wife sale. They were public affairs, usually taking place during market days. There was usually a pre-arranged buyer, someone the wife already knew and with whom she may already be involved. The sale itself was handled like any livestock sale, with the wife led to market in a halter. By the late 18th century, it became common practice to include a deed of sale, transferring all obligations of support to the purchaser. These deeds were not legal, but helped reinforce the public nature of the ritual.

After I had written the opening scene of The Bride Sale, depicting the auction, I came across the French print, above, c1820, using a wife sale to poke fun at the perceived mercenary nature of the British. It showed exactly what I had envisioned, with the wife perched on a platform, above the other “livestock”, with a halter around her neck.

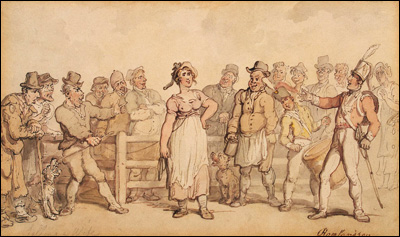

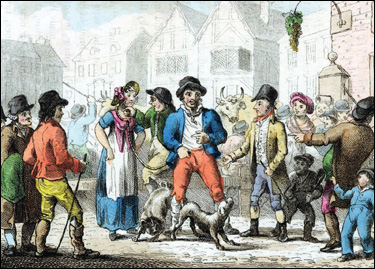

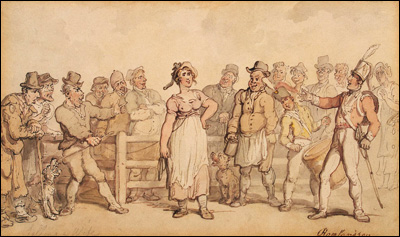

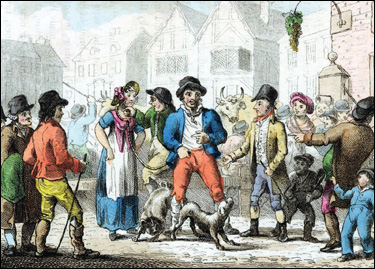

More recently, I discovered the print by Thomas Rowlandson, right, which shows a similar scene of a haltered woman being sold at auction. The only difference in the scene I imagined for The Bride Sale is that the tethered wife is not so obviously willing to be sold. The 1816 print below from Popular Past Times (“Selling a Wife to the Highest Bidder”) shows a somewhat more reluctant wife.

The fact that there are prints showing the practice of wife-selling, especially by the very popular Rowlandson, must indicate that it was a situation the general populace would recognize, that a woman being led by a halter was understood to be a wife for sale. Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge, written in 1886, opens with a drunken man selling his wife and child to the highest bidder.

* * *

When deciding on the setting for The Bride Sale I knew I needed someplace that would look very different to the heroine from the lush, green countryside where she’d grown up. The granite moorland of mid-Cornwall seemed most appropriate. I always try to find real houses to use as inspiration, if not true models, for any house used in my stories. I wanted the hero’s house in Cornwall to look as forbidding to the heroine as he did. I settled on Cotehele, an Elizabethan house on the eastern border of Cornwall, as my model.

I visited the house on a bleak day in late November, exactly the time of the book’s opening (see above). The house was not open for visitors but I got to wander the grounds and all about the exterior. The Great Hall was being decorated for Christmas by some of the gardening staff. They were hanging huge boughs made of Cotehele greenery and dried flowers that would drape in deep swags from each corner of the room to the center. The staff kindly let me step into the Great Hall briefly and watch their work.

“Selling a Wife” by Thomas Rowlanson c1812.

“Selling a Wife To the Highest Bidder” 1816.

Cotehele, exterior

Cotehele, the Great Hall

ORDER YOUR OWN COPY

Digital Format in the US:

Digital Format in the UK:

In Print:

- Sorry, this title is not currently available in printed formats

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may

use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.