When ladies (and gentlemen) appeared at Court on formal occasions they were required to wear Court Dress, which was a very formal, very specific type of garment that was not worn anywhere else.

Rules of Court Dress were rigid and dictated by the current monarch or his Queen. During the Regency, those rules produced a type of female garment that appears perfectly ridiculous to modern eyes, but which was taken quite seriously by those who wore them and by the designers who made them.

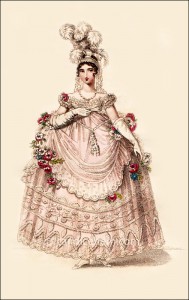

The rules of Court directed that ladies should wear skirts with hoops and trains, and that white ostrich feathers be worn in the hair, attached to lappets which hung below the shoulders. These rules had been in place long before George III took the throne. In his predecessor’s day the skirts were enhanced with panniers that stood out very wide on either side, but leaving the front and back flat. The intent of such odd-looking dresses was to display a broad swath of beautifully embroidered fabric, some of which had pictorial or floral scenes that used the entire front of the skirt as a canvas. Side panniers had been replaced by normal round hoops by the time George III came to the throne in 1760. In the last decade of the 18th century, the fashion for wide skirts began to evolve into the slim, vertical line associated with Regency dress. Queen Charlotte, however, held firm on the rules of Court Dress, and ladies were forced to adapt those rules to the current style, which produced a very odd-looking garment with the high-waist under the bosom and a full hoped skirt.

Who wore these silly (to my eye) concoctions?

Wives and daughters of peers, members of parliament, or the landed gentry were allowed to be formally presented at Court on only three specific occasions: as a young woman making her debut in Society (she was later to be called a debutante), upon her marriage, and on the occasion of her husband having an honor conferred upon him.

For daughters, the presentation at court marked them as suitable bridal candidates in the marriage market. For wives, it marked them as respectable members of the upper classes of Society and sometimes opened doors for them that had formerly been closed. The woman being presented was always sponsored by another woman who had already been presented. This was usually her mother or mother-in-law or another female relation. If she had no relative to present her, there were certain high-ranking ladies who would do so for a fee.

The presentations took place at St. James’s Palace at events called Drawing Rooms, where the monarch and/or his Queen received those attending Court. Presentation Drawing Rooms were held two or three times a week during the Season. Based on letters and diaries of the time, it was so stressful an experience that it was regarded more as a duty than a pleasure. The young woman to be presented stood sometimes for hours (one never sat in the presence of the Queen) waiting for her name to be announced by the Lord Chamberlain. She then walked to where the Queen sat and made a deep curtsy — which had been practiced and practiced while wearing the hooped skirt. A few pleasantries were exchanged, the young woman answering any question the Queen put to her, but no more. When the Queen indicated she was dismissed, the young woman made one more deep curtsey, and then had to walk backwards out of the royal presence (one never turned one’s back on the Queen) all the while dealing with the obstacle of her train so as not to trip over it. Stressful indeed!

Other formal occasions requiring Court Dress were the Drawing Rooms held to commemorate the Queen’s birthday (January) and the King’s birthday (June). These were invitation-only events involving only the highest-ranking members of Society. Unlike the young women being presented at court for the first time, whose dresses were primarily white or pale pastel shades, the ladies of the nobility were allowed more freedom of color in their court costumes. Many of the magazines of the period listed all the important women who attended the Drawing Rooms and described what they wore. For example, in January 1809, the Lady’s Magazine reported that the Countess of Carlisle wore: “A most superb dress of ruby velvet and white satin; the draperies in every part trimmed with a rich imperial gold border, and a profusion of splendid gold tassels, rope, &c.; robe trimmed with point lace. Head-dress, ruby turban, jewels, and feathers.” Figure 2 shows a dress worn by the Marchioness of Townshend at the Queen’s Drawing Room in 1806, and Figure 6 shows what Lady Worsley Holmes wore to the King’s Drawing Room in 1820.

The Queen’s unyielding insistence that women attend court in unfashionable hoops continued even after the King no longer appeared in public, and Drawing Rooms were hosted by the Prince Regent. The ever astute Mrs. Bell (the shameless self-promoter who designed most of the dresses illustrated in La Belle Assemblée) at last came to the rescue with a more flexible hoop in 1817 (see Figure 5 – click on the image to read more about the new hoop), but it must still have been something of an aggravation to deal with such an unwieldy and heavy costume while standing, never sitting, at court. Such out-of-date dress had long been discarded at the French court, where no hoops were worn, but where long trains, white plumes, and court lappets echoed the English court style. (See Figure 4.) After the Bourbons reclaimed the French throne upon Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, fashion magazines in England began to include prints of French court dress. It is tempting to believe they did so to encourage the Prince Regent to adopt a more current style of court dress by showing the more fashionably attired ladies of the French court. These prints, including the one from La Belle Assemblée in Figure 4, were often exact copies of fashion prints that had previously appeared in the popular French publication, Le Journal des Dames et Des Modes.

The Prince, however, did not relax the rules until he came to the throne as George IV in 1820. Finally, ladies could abandon their hoops. (Ironically, they came back into fashion within another 15 years.) The rules regarding white plumes in the hair still held fast (and did so well into the 20th century), and in looking at the fashion prints of the early 1820s, it appears that the extravagance of skirt that was given up with the hoop was transferred to the head. Plumes became ridiculously large and numerous. Figure 6, which shows one of the first non-hooped Court Dresses from 1820, also exemplifies the new extravagance for plumes. Fortunately, ostrich feathers weigh very little, else the lady would surely have been unable to lift her head.

If it is any consolation to the ladies, the rules of gentlemen’s court dress were much more strict, and became even more so during Victoria’s reign.

For more information on court dress, see these sources:

- Nigel Arch and Joanna Marschner, Court Dress Collection, Kensington Palace, 1984.

- Sharon Laudermilk and Teresa L. Hamlin, The Regency Companion, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989.

- Philip Mansel, Dressed to Rule, Yale University Press, 2005.

- Kay Standiland, In Royal Fashion, Museum of London, 1997.

For more information on fashion prints, see these sources:

- Alison Adburgham, Women in Print: Writing Women and Women’s Magazine from the Restoration to the Accession of Victoria, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1972.

- Irene Dancyger, A World of Women: An Illustrated History of Women’s Magazines 1700-1970, Gill and Macmillan, 1978.

- Jody Gayle, Fashions in the Era of Jane Austen, Publications of the Past, 2012.

- Madeleine Ginsburg, An Introduction to Fashion Illustration, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1980.

- Vyvyan Holland, Hand Coloured Fashion Plates 1770-1899, Batsford, 1955.

- Doris Langley Moore, Fashion Through Fashion Plates 1771-1970, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1971.

- Sacheverell Sitwell and Doris Langley Moore, Gallery of Fashion 1790-1822, Batsford, 1949.

- Cynthia L. White, Women’s Magazines 1693-1968, Michael Joseph, 1970.